William Dalrymple (historian)

Tutub | |

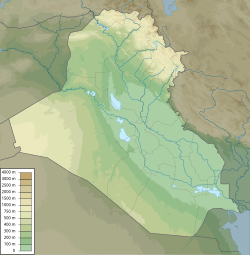

| Alternative name | Khafaje |

|---|---|

| Location | Diyala Governorate, Iraq |

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 33°21′16.83″N 44°33′20.71″E / 33.3546750°N 44.5557528°E |

| Type | tell |

| History | |

| Periods | Uruk, Jemdet Nasr, Early Dynastic, Akkadian, Isin-Larsa |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1930–1938 |

| Archaeologists | Henri Frankfort, Thorkild Jacobsen, Pinhas Delougaz |

Khafajah or Khafaje (Arabic: خفاجة), ancient Tutub, is an archaeological site in Diyala Governorate, Iraq 7 miles (11 km) east of Baghdad. Khafajah lies on the Diyala River, a tributary of the Tigris. Occupied from the Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods through the end of the Old Babylonian Empire, it was under the control of the Akkadian Empire and then the Third Dynasty of Ur in the 3rd millennium BC. It then became part of the empire of the city-state of Eshnunna lying 12 miles (19 km) southwest of that city, about 5 miles (8.0 km) from the ancient city of Shaduppum, and near Tell Ishchali, both which Eshnunna also controlled. It then fell to First Babylonian Empire before falling into disuse. The city of Tutub is mentioned in a fragmentary Sumerian temple hymn "... To the shrine Nippur, to the Duranki <we go>, To ..., to the brickwork of Tutub <we go>, To the lofty Abzu ...".[1]

Archaeology

Khafajah was excavated for 7 seasons between 1930 and 1937 by an Oriental Institute of Chicago team led by Henri Frankfort with Thorkild Jacobsen, Conrad Preusser and Pinhas Delougaz. Before the work began looters had dug a large number of deep pits at various points in the site. Many artifacts from these illicit digs ended up in various museums and private collections in the decades preceding the start of excavations.[2][3][4][5][6][7] For two seasons, in 1937 and 1938, the site was worked by a joint team of the American Schools of Oriental Research and the University of Pennsylvania led by Delougaz.[8] They worked primarily in the Nintu temple on mound A (along with the cemetery to the east and northeast of the temple) and with soundings on mound B.[9][10] Among the small finds at the site was an Akkadian period die.[11] and a terracotta incantation bowl written in "typical Jewish Babylonian Aramaic of the Sasanian period".[12]

The site consists of four mounds, labeled A through D.

Mound A

The main one, Mound A which lies 4 meters above the plain, extends back as far as the Uruk period and contained a large oval temple, a temple of the god Sin, and a small temple of Nintu (where a bearded cow statue was found), dating back to the Jemdet Nasr and Early Dynastic periods. An early radiocarbon date for the first level of the Sin Temple returned a corrected date of 4963 BC which is thought to be somewhat too early and possibly contaminated.[13] The mound was occupied through the Akkadian Empire period and then abandoned. Its name, Tutub, is not known before the Akkadian times. A number of vaulted tombs made out of plano-convex bricks were found.[14] About 70 Akkadian Period cuneiform tablets were found there. Most of the tablets were administrative in nature and were apportioned half to the Oriental Institute and half to the Baghdad Museum.[15][16] A defensive wall surrounding Mound A was encountered in a number of places with a width of 6 to 8 meters and unknown full extent. It was not fully excavated so the dating is uncertain.[17]

A large number of private houses were excavated on Mound A, almost all from the Early Dynastic period. At the lowest point above the water table were some homes of the "Protoliterate period". Finds there included a numerical tablet (Kh. V 338) dated to the Uruk V period c. 3500 BC. Other small finds from that level included stone stamp seals, clay figurines, a stone macehead, and four cylinder seals. At the top level foundations of Akkadian Empire period residences were excavated. An enormous number of small finds emerged from the Early Dynastic period homes including many cylinder seals, faience and lapis lazuli beads, metal tools and other metal objects, spindle whorls, stone weights, figurines, pendants, amulets, clay model chariot wheels, and a number of cuneiform tablets. A number of Early Dynastic burials, 168 in total and mostly intramural (inside homes) with a few having multiple skeletons, were excavated. Burials were mostly inhumations with simple grave goods, mainly pottery but with the occasional cylinder seal, copper tool, etc. There were also 4 Plano-convex brick tombs and 24 Plano-convex brick vaulted tombs some holding much more extensive grave goods.[17] A notable residence find (Kh. IX 87) was a hoard of hacksilver found sealed in a jar in the courtyard of a home dated to the Early Dynastic IIIa period. It contained 14 silver spiral rings, 15 silver beads, 2 silver cones, silver ring and 14 fragments of silver rings and wire, 13 fragments of silver foil, a silver ingot, 9 silver strips and 30 pieces of melted-down silver and scraps. The items were divided between the Baghdad Museum and the Penn Museum.[18]

Mound A Temples

Five religious structures were found on Mound A, the Temple Oval, and located to the east of the Temple Oval and north of the summit of the Mound, Large Temple ("Sin Temple"), Small Temple, Nintu Temple, and Small Single Shrine, all within a 100 square meter area:[19][20]

Temple Oval - The Temple Oval had three building phases, all in the Early Dynastic period. A few partial Akkadian Empire period inscriptions were found indicating it remained in use at least for a time in that period. The Temple Oval bears may similarities to the contemporary temple of Ninḫursaĝ at Tell al-'Ubaid.[21][22] [23][24]

- Phase 1 - Before construction began on the Temple Oval the surface was cleared and at least 7 meters of pure sand was laid down extending to the limit of the outer enclosure wall. The full depth of sand was unclear as the water table was reached at this point. The sand layer was shown to cut into earlier residential structures. The sand was sealed by a packed clay layer put down by building 1.2 meter walls for all planned structures, including the inner and outer enclosure walls, and then packing the spaces with wet clay. The outer enclosure wall ran for 300 meters with a 3 meter wide foundation and 1.5 meter wall width, with added interior buttresses. The inner enclosure had a 4.5 meter foundation width. The entrance to the Temple Oval lay in the northwest. For much of the oval the two walls were about 5 meters apart (ranging from 3 to 8 meters). This gap became much wider in the northwest allowing room for a building deemed "House D" and a 450 square meter forecourt. Various small rooms were also found in this space. House D is thought to have been the residence of the temple's priests or possibly the high priest as ruler of the city. Within the inner enclosure the large courtyard held two 2.5 meter wide wells lined with plano-convex bricks and a stepped altar with a jar deposited at the corner, the altar being part of a 25 meter by 30 meter buttressed platform. A series of room, about 18 in total, lined the inner enclosure wall extending up to the walls defining the courtyard. Several of them are thought to have been shrines. Finds in these rooms included a painted pot of the Jemdat Nasr period (Kh. IV 473) which was deemed to be a heirloom rather than contemporary with construction and 3 copper sculptures (Kh. I 351a-c), buried against the inner enclosure wall, one with a trace of inscription. There were three occupation levels in the phase and only minor changes were made in the Temple Oval during that period. Small finds included 12 cylinder seals and many maceheads.[21]

- Phase 2 - Built directly on the leveled Phase 1 building. Only minor changes were made within the oval, with the construction being of somewhat lower quality. The outer enclosure wall was widened from 1.5 meters to 3 meters and buttresses (0.5 meter deep and 2.3 meters wide with an average gap of 5 meters) were added to the outer side. The inner enclosure wall was rebuilt as before. In the courtyard preserved footprints of people and animals were found, indicating the area was not roofed. Two foundation deposits were found by the courtyard platform. One with "one dark millstone (metate) and rectangular pieces of gold, copper, lapis lazuli, crystal, and slate (Kh. IV 425)" and the other "comprised the same materials (Kh. IV 427), with the exception of an unworked piece of carnelian (Kh. IV 426) instead of crystal, and it contained also a nail with flower shaped head (Kh. IV 428), a copper tool (Kh. IV 429), and a piece of bronze wire". In House D finds included "two small pots filled with very small beads of lapis lazuli, agate, and gold as well as some larger lapis lazuli beads and a few copper rings were found near by". Small finds included 11 cylinder seals, maceheads, and small metal objects.

- Phase 3 - Relatively poorly preserved but showing that there were only minor changes. An inscribed macehead (Kh. I 636) "Shar-ilumma, chief alderman, fashion[ed the mac]e(?); to Inanna he presented (it)" was found between the Phase 2 and 3 layers and interpreted as a burial. Bowl fragments bore inscriptions of Rimush, a ruler of the Akkadian Empire including "To Sin did Rimush, king of Kish, when Elam and Barahshe he had smitten, from the booty of Elam present (thi)". Two cylinder seals were found.[21]

Large Temple (10 phases) - generally called the "Sin Temple". It had five building phases in the Uruk period and five in the Early Dynastic period.[25] It is generally ascribed to the god Sin because a statue (Kh. IV 126) was found, on the next to latest level, inscribed "Urkisal, šangû-priest of Sin of Akshak, son of Nati, pāšišu-priest of Sin, for protection has presented (this)". The attribution is otherwise uncertain and an alternate reading of the inscription would make the god Salam (Shamash). A more recent interpretation of this is "(dSAḠ.MÙŠ = dsa12-mùš) and connects the deity with dsa-mu-UŠ".[26] The excavators declared "while we retain the latter familiar name, it should be made clear that it may not be correct and that the identity of the deity to whom this temple was consecrated still remains uncertain". The level below the temple had a number of beveled rim bowls (rare at higher levels) and clay decorative cones.[27]

- Phase 1 - a 13.50 meter by 9 meter tripartite building with a long central cella/sanctuary (3 meters by 11.70 meters) and small rooms on either side all built of "Riemchen" sundried bricks. The doorways were on the northeast side and a stepped platform, thought to be an altar, was in the northwest part of the cella. A stairway in one of the side rooms led to the roof. Finds on this level include two inlaid stone pendants.

- Phases 2 and 3 - completely rebuilt though mostly keeping to the original plan. The roof to the stairway moves to the front which becomes a courtyard area. Finds included a hoard of cylinder seals including Kh. VII 274 on Level 2. On Level 3, by the altar, were found seals, animal amulets, pendants, a stone vase inlaid with jasper and mother-of-pearl, a pottery libation vase in the form of a bird, and small gold crescent.

- Phase 4 - a major rebuild with the temple cleared to foundation stubs, new thicker 1 meter high walls built on those stubs and the enclosed area packed with clay to form a platform. The new temple, again built with "Riemchen" sundried bricks, is very similar to that of the earlier phases. Several rooms are added to the east side of the courtyard. There were four occupation levels in the phase. Finds included pendants, amulets, and seals, a small female statue in the round. One of the cylinder seal made of bitumen and sheathed with copper and the amulets included the "eye" or "hut" type found at other sites. A 3 meter wide and 4.5 meter long bitumen coated stairway with balustrades from the courtyard led to the temple. By this time the western room has fallen out of use.

- Phase 5 - courtyard and area to its east raised to match the temple. Double-recessed niches added to the cella. Finds included a hoard of beads in their original string order with bull pendants at each end.

- Phase 6 - temple rebuilt as before with the altar being enlarged. A large area to the east of the temple, formerly holding residential type buildings, is raised to the level of the temple and made part of the temple precincts with a large enclosure wall. It was accessed by a single door in the east wall of the cella. Finds from this phase were sparse.

- Phase 7 - temple rebuilt as before, though with 2.5 meter thicker foundation walls on the north and east sides, after a layer of reed mats was laid down on the cleared surface. On the east the foundation extension supported two corner towers flanking the main entrance. There was two occupation levels with minor modifications made in the temple in the second. Finds from this phase were sparse.

- Phase 8 - large 60 to 90 centimeter foundations were dug before rebuilding, not respecting earlier construction, and much thicker walls were used. The west side of the temple was lengthened by 2 meters and the cella extended to 15 meters and its packed earth floor replaced by plano-convex mudbricks. Most of the finds from the western area of the temple and courtyard had been removed by modern looters but the eastern portions provided a miniature gold bull, seals, amulets, and a wheeled terracotta house model topped by a "fruit stand". This phase had 3 occupation levels.

- Phase 9 - significantly damaged by modern looting though enough remained to indicate no significant changes. No cylinder seals were found, only stamp seals. Five occupation levels. Indications of conflagration and a period of dis-use after this phase.

- Phase 10 - even more robber hole damage. The temple plan was largely as before, though extended somewhat in the western direction. Occupation of the Large Temple ends at this point.

Nintu Temple - Consisted of three sanctuaries and two intervening courtyards. It had an irregular shape and was about 43 meters east to west and about 30 meters north to south. Only partly excavated below phase 6 aside from one sanctuary which was completely cleared. Named after Nintu based on a single inscription, "To Nintu. . . . , child of Damgalnun, has É:KU(?):A(?), child of Amaabzuda, presented (this)", though the excavators proposed that three gods including Damgalnun were worshiped there and that Damgalnun may be an epitaph of the goddess Ninhursag. The temple had seven building phases.[19]

- Phase 1 and 2 - sanctuary is small with thin walls and generally not an impressive building.

- Phases 3 - sanctuary becomes shorter and wider though better constructed. In phase 3 green stone vase (Kh. IX 19) was found embedded in the plano-convex brick altar. In the court in front of the sanctuary a large (80 centimeter) perforated pottery disk was found, thought to be a pottery wheel.

- Phases 4 though 7 - same plan throughout though the last level was heavily damaged by later residential buildings. Phase 5 is notable by the find, near the altar, of a large buried hoard of statuary described by the excavators as "depository for some discarded cult objects".[28] A notable find, from Phase 6 was a bronze statuette of wrestlers balancing jars on their heads (KH. VIII 117). One sanctuary (2.70 meters by 12 meters) had an elaborate altar at one end. Embedded in the alter were a bearded cow (Kh. IX 123), a human-headed bull (Kh. IX 124), and several maceheads. Altars in the other sanctuaries also had embedded statuary.

Small Temple - lies about halfway between the Temple Oval and Large (Sin) Temple and is around 20 meters by 10 meters in maximum extent with 9 or 10 phases and built of plano-convex bricks. Finds were few in number most notably including a green stone vase carved in low relief (Kh. V 14) and a painted pottery libation vase in the form of a bird (Kh. V 173). The deity of the temple is unknown.[19]

- Phases 1 to 5 - a modest single room with an antechamber with an altar at the narrow northern end. Minor changes, primarily noted in the altar shape and size.

- Phases 6 to 9/10- Major changes in Phase 6 are part of a wide ranging building program which included Phase 8 of the Large (Sin) Temple and initial work on the Temple Oval. The sanctuary, now much thicker walls and foundations and gained a courtyard with circular offering tables on one side and a room on the other side (without foundations). The altar extends the entire width of the room. In the remaining phases walls become thinner, there are changes to the size and shape of the altar, and the courtyard gains two more circular offering tables.

Small Single Shrine - a single period temple somewhat damaged by later building and by erosion (being on the uppermost level of Mound A). Its size was roughly 9 meters by 4 meters with an altar and adjacent circular offering table on the northeast wall. The excavators believed to be an isolate shrine and not part of a larger religions area and definitely dated it to the Early Dynastic III period.

Other Mounds

The other 3 mounds lie about half a mile west of Mound A. The excavators focus was on the "pre-Sargonid" period so these mounds, having later occupation, received much less attention.

- Mound B - The mound lies 6 meters above the plain. A number of robber pits with the eastern slope heavily dug out by looters. The Old Babylonian period Dur-Samsuiluna fort, built during the reign of ruler Samsu-iluna (c. 1750–1712 BC), was found here. The mound also showed signs of Hurrian presence.[29] The fort is around 1000 square meters in area with a large administrative of palace building and a smaller "gate room" and is surrounded by a 4.7 meter wide fortification wall (with 6 meter wide buttresses every 10 to 12 meters) and was identified based on an inscribed cylinder found as a foundation deposit in the "gate room". Inscriptions from the 24th year of Samsu-iluna marking the building of this fort were found on this mound and on Mound C. There were very few finds and it is unclear if there was earlier occupation as primarily the excavators only traced walls on this mound and left rooms uncleared.[30][31]

- Mound C - The mound lies 5 meters above the plain. Only two soundings were conducted. Some pottery traces from the Old Babylonian and Kassite periods were noted. Bronze finds included many bronze spear blades, sickles, hoes, arrowheads, and needles. Epigraphic finds were ten Old Babylonian cylinder seals and one sealing.

- Mound D - The mound lies 4 meters above the plain. This mound was surrounded by a 6.5 meter thick fortification wall (buttressed to 12 meters) with towers at inflection points and a niched fortified gate with a projecting tower. It took the form of an irregular polygon over 200 meters long and over 150 meters wide. A large number of baked clay mace heads and sling bullets were found in front of the gate. In the center of the enclosed area was a large well constructed building identified as a temple of the god Sin. A number of Old Babylonian archive tablets were found there in two heaps. Other finds included three cylinder seals, a duck weight, and many terracotta plaques. The temple had two building periods with the first being 45 by 75 meters and the later 28 by 45 meters within the earlier construction. It is not known if the newer construction fully replaced the earlier or was used simultaneously. Under the older construction a number of large baked brick vaulted tombs, robbed in antiquity, were found. It is unknown if the mound was occupied before the Isin-Larsa period.[32]

Stratigraphy and Chronology

The Khafajah dating and stratigraphy of the excavators has largely held up well over time but in later years there have been proposals to make some adjustments on Mound A. As opposed to the original interpretation of the Large "Sin" Temple as having five Uruk III (Jemdat Nasr) periods followed by five in the Early Dynastic it has been proposed that only the first 2 or 3 were dated to Uruk 3 (or even moved the first 4 phases into Early Dynastic I). There are similar minor shifts proposed for the smaller temples. The dating of the Temple Oval is somewhat more complicated, reflecting the chronology of the Early Dynastic period in Mesopotamia currently being in a state of flux. The excavators dated Phase 1 of the Temple Oval to early in Early Dynastic I period. Various proposals have moved that slightly earlier or later. The excavators had the Temple Oval falling out of use in the Early Dynastic IIIa period. Some proposals move the end to the Early Akkadian Empire period or even move all of building Phase 3 into the Akkadian Empire period (based on the assumption that some burning noted in the phase transition reflected the takeover of Khafajah by the Akkadian Empire. All these are still open issues.[33][34][35][36][37][38]

History

Late Chacolithic

Because of the current local water table excavators did not reach virgin soil finding 4.5 meters of Protoliterate (Uruk V, Uruk IV, and Uruk III ie Jemdet Nasr) to that point. Pottery from the period (including beveled rim bowls) supported the stratigraphy and a Uruk V period numerical tablet was found. The large temple on Mound A, generally called the Sin Temple, was constructed and rebuilt several time in the Uruk period.[39]

Early Bronze

Khafajah was occupied Early Dynastic Period. On mound the Temple Oval was rebuilt twice during the period and the other temples there were also rebuilt.

Akkadian period

Naram-Sin of Akkad named his son Nabi-Ulmash governor of Tutub.[41] A fragment of a statue of the Akkadian ruler Manishtushu was found there.[42] Two stone bowl fragments with the name of the Akkadian ruler Rimush were found near the Temple of Sin.

"T[o] the god S[in], RI[mus], ki[ng of] the wo[rld], wh[en he conquered Elam and Parahsum], [dedicated (this bowl) from the booty of Elam]" [43]

Ur III period

Some point after the fall of the Akkadian Empire, "Awal, Kismar, Maskan-sarrum, the [la]nd of Esnunna, the [la]nd of Tutub, the [lan]d of Simudar, the [lan]d of Akkad" briefly came under the control of Puzur-Inshushinak of Elam as the first Third Dynasty ruler, Ur-Nammu, reports liberating those cities.[44] The site was also reported to be captured by ruler Shulgi (c. 2094 – 2046 BC) of the Third Dynasty in his 30th year. It then came under the control of Eshnunna in the Isin-Larsa period. The fifth year name for Eshnunna ruler Nūraḫum was "Year Tutub was seized". This was considered a significant event as the following year was named "Year after the year Tutub was seized". Tutub also appears in a Ur III taxation record.[45]

Middle Bronze

Some obscure rulers, Sumuna-jarim, Tattanum, Hammi-dusur are known to have controlled Tutub at some point early in this period. It is uncertain if they were local or non-local rulers. Abdi-Erah of the Manana Dynasty ruled Tutub at some point. One local ruler, Abi-matar, is known from six year names including "Year in which Abi-matar brought a ruddy copper statue into the temple of Sin".[46][47] A later ruler of Eshnunna, Warassa, had the cryptic year name "Year Tutub was restored". Later, after Eshnunna was captured by Babylon, a fort was built at the site by Samsu-iluna in his 24th year of rule (c. 1726 BC) of the Old Babylonian Empire and named Dur-Samsuiluna, his year name saying "he erected Dur-Samsu-iluna in the land of Warum on the banks of the canal (called) 'Turran (Diyala)'".[48]

The history of Khafajah is known in somewhat more detail for a period of several decades as a result of the discovery of 112 clay tablets (one now lost) in an Old Babylonian period temple of Sin at Mound D. The recovered portion of the temple archive dates from roughly 1820 BC to about 1780 BC (based on rulers named) when Tutub was for the most part controlled by Eshnunna. The tablets constitute part of an official archive of the ēntum-priestess of the temple and include mostly loan (generally of barley or silver) and legal documents. The temple also purchased slaves, including self slaves and sales of children, as a result of loan defaults.

"17 shekel of silver for the redemption of Hlagalija, his father, Zagagum has received (as a loan). (But) he had no silver (with which to repay the loan), (so) he so[ld] himself to the enum-priest. [He (the seller) has transferred] the bukannum. [break of about three lines] Witnesses."

The Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures (formerly the Oriental Institute of Chicago) holds 57 of the tablets with the remainder being in the Iraq Museum.[49][50][51] An additional 21 Tutub tablets, presumably looted, were purchased by the Oriental Institute Museum and later published. They are thought to be dated about 50 years later have come from Mound B, the site of Dur-Samsuiluna.[52] Fifteen Tutub tablets, from a private donor, are held by the Hearst Museum and 6 have been published.[53] A few other Tutub tablets in other collections have also been published.[54][55]

Gallery

The Iraq Museum's Sumerian Gallery displays several Sumerian statues from the Temple of Sin and the Temple of Nintu (V and VI), including part of a hoard found at the Nintu Temple. Some finds are also housed at the Sulaymaniyah Museum.

-

Female worshiper, Sin Temple, Khafajah, Iraq Museum

-

Female worshiper, Sin Temple, Khafajah, Iraq Museum

-

Statue from the Sin Temple, Khafajah, Iraq Museum

-

Statue from the Temple of Sin at Khafajah, Iraq Museum

-

Statue from the Hoard of Nintu Temple V at Khafajah, Iraq Museum

-

Statue from the Hoard of Nintu Temple V at Khafajah, Iraq Museum

-

Male statue from Hoard in Nintu Temple V at Khafajah, Iraq Museum

-

Statue from Nintu Temple VI at Khafajah, Iraq Museum

-

Male statuette, Nintu Temple VI, Khafajah, Iraq Museum

-

Male statuette, Sin Temple IX, Khafajah, Iraq Museum

-

Male statuette, Nintu Temple VI, Khafajah, Iraq Museum

-

Limestone human head found at Khafajah, Early Dynastic II (c. 2700 BC)

-

Cylinder seal found at Khafajah, Jemdet Nasr period, (3100–2900 BC)

-

Three Sumerian statues, Early Dynastic Period, 2900-2350 BC, from Khafajah, Iraq. The Sulaymaniyah Museum

-

Head of a Sumerian female, from Khafajah, excavated by the Oriental Institute, Early Dynastic III, c. 2400 BC. The Sulaymaniyah Museum

-

Headless statue of a Sumerian man, from Khafajah, Early Dynastic Period, 2900-2350 BC. The Sulaymaniyah Museum

-

Dice from Khafajah Akkadian period

-

Pull toy, Khafajah, Temple Oval II, Early Dynastic period, 2900-2330 BC, baked clay - Oriental Institute Museum

-

Large pottery jar used for ritual purposes (omens). Sin Temple, Khafajah, Iraq. Early Dynastic period, 2600-2370 BC. Iraq Museum

See also

References

- ^ Sjöberg, Å. W., "Miscellaneous Sumerian Texts, II", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 3–45, 1977

- ^ [1] The Diyala Project at the University of Chicago

- ^ [2]Henri Frankfort, Thorkild Jacobsen, and Conrad Preusser, "Tell Asmar and Khafaje: The First Season's Work in Eshnunna 1930/31", Oriental Institute Communications 13, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1932

- ^ [3]Henri Frankfort, "Tell Asmar, Khafaje and Khorsabad: Second Preliminary Report of the Iraq Expedition", Oriental Institute Communications 16, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1933

- ^ [4]Henri Frankfort, "Iraq Excavations of the Oriental Institute 1932/33: Third Preliminary Report of the Iraq Expedition", Oriental Institute Communications 17, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1934

- ^ [5]Henri Frankfort with a chapter by Thorkild Jacobsen, "Oriental Institute Discoveries in Iraq, 1933/34: Fourth Preliminary Report of the Iraq Expedition", Oriental Institute Communications 19, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1935

- ^ [6]Henri Frankfort, "Progress of the Work of the Oriental Institute in Iraq, 1934/35: Fifth Preliminary Report of the Iraq Expedition", Oriental Institute Communications 20, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1936

- ^ Speiser, E. A., "New Discoveries at Tepe Gawra and Khafaje", American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 190–93, 1937

- ^ Speiser, E. A., "Progress of the Joint Expedition to Mesopotamia", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 70, pp. 3–10, 1938

- ^ Speiser, E. A., "Excavations in Northeastern Babylonia", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 67, pp. 2–6, 1937

- ^ Shafer, Glenn, "Marie-France Bru and Bernard Bru on Dice Games and Contracts", Statistical Science, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 277–84, 2018

- ^ Cook, Edward M., "An Aramaic Incantation Bowl from Khafaje", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 285, pp. 79–81, 1992

- ^ [7]Lawn, Barbara, "University of Pennsylvania radiocarbon dates XV", Radiocarbon 15.2, pp. 367-381, 1973

- ^ [8]H.D. Hill, T. Jacobsen, P. Delougaz, .A. Holland, and A. McMahon, "Old Babylonian Public Buildings in the Diyala Region: Part 1 : Excavations at Ishchali, Part 2 : Khafajah Mounds B, C, and D", Oriental Institute Publication 98, Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 1990 ISBN 0-918986-62-1

- ^ [9] I.J. Gelb, "Sargonic Texts from the Diyala Region", Materials for the Assyrian Dictionary, vol. 1, Chicago, 1961

- ^ Sommerfeld, W., "Die Texte der Akkade-Zeit. 1. Das Dijala-Gebiet: Tutub", (IMGULA 3). Münster: Rhema, 1999

- ^ a b [10]Pinhas Delougaz, Harold D. Hill, and Seton Lloyd, "Private Houses and Graves in the Diyala Region", Oriental Institute Publications 88, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1967

- ^ Hafford, W. B., "Money in Mesopotamia Revisited: An Early Dynastic Silver Hoard from Khafaje", Archaeology from Every Angle: Papers in Honor of Richard L. Zettler, pp. 111-138, 2024

- ^ a b c [11] Pinhas Delougaz and Seton Lloyd with chapters by Henri Frankfort and Thorkild Jacobsen, "Pre-Sargonid Temples in the Diyala Region", Oriental Institute Publications 58, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1942

- ^ [12]Ann Louise Perkins, "The Comparative Archeology of Early Mesopotamia", Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 25, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1949

- ^ a b c [13]Pinhas Delougaz, with a chapter by Thorkild Jacobsen, "The Temple Oval at Khafajah", Oriental Institute Publications 53, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1940

- ^ [14]Havé, Amaury, "Houses divided: The stratigraphy of Khafajeh’s ED III residential neighbourhoods around the Oval Temple", 13th International Congress on the Archaeology of Ancient Near East (ICAANE 13), 2023

- ^ Vallet, Régis, "Le Temple Ovale de Khafajeh: histoire et insertion urbaine", Archimède 9, pp. 239‑49, 2019

- ^ Quenet, Philippe, "Reconstructing the Temple Oval of Khafajah. Insight into the Emergence of Multi-Stepped Terraces", in The Old Babylonian Diyala: Research since the 1930s ans Prospects, 2018

- ^ [15]Henri Frankfort, "Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region", Oriental Institute Publications 72, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1955

- ^ Marchesi, G. and Marchetti, N., "Royal statuary of Early Dynastic Mesopotamia", MC 14, Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake, IN, 2011

- ^ [16]Henri Frankfort, "Sculpture of the Third Millennium B.C. from Tell Asmar and Khafajah", Oriental Institute Publications 44, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1939

- ^ [17]Henri Frankfort., "More Sculpture from the Diyala Region", Oriental Institute Publications 60, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1943

- ^ Speiser, E. A., "Mesopotamian Miscellanea", Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 68, pp. 7–13, 1937

- ^ [18] Lambert, Wilfred G., and Mark Weeden, "A statue inscription of Samsuiluna from the papers of WG Lambert", Revue d’assyriologie et d’archéologie orientale 114.1, pp. 15-62, 2020

- ^ Poebel, Arno, "Eine sumerische Inschrift Samsuilunas über die Erbauung der Festung Dur-Samsuiluna", Archiv für Orientforschung 9, pp. 241-292, 1933

- ^ Allen, Francis O., "The Oriental Institute Archaeological Report on the Near East: Fourth Quarter, 1935", The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures, vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 201–14, 1936

- ^ Gibson, McGuire, "A Re-Evaluation of the Akkad Period in the Diyala Region on the Basis of Recent Excavations at Nippur and in the Hamrin", American Journal of Archaeology 86(4), pp. 531-538, 1982

- ^ Gibson, McGuire, "The Diyala Sequence : Flawed at Birth", in Between the Cultures: The central Tigris region from the 3rd to the 1st millennium BC. Conference at Heidelberg, January 22nd - 24th, 2009, Heidelberger Studien zum alten Orient, édité par P. A. Miglus et S. Mühl. Heidelberg: Heidelberger Orientverlag, pp. 59‑84, 2011

- ^ Dittmann, Reinhard, "Genesis and Changing Inventories of Neighborhood Shrines and Temples in the Diyala Region. From the Beginning of the Early Dynastic Period", in It’s a long way to a historiography of the Early Dynastic Period(s), Altertumskunde des Vorderen Orients, édité par R. Dittmann, G. J. Selz, et E. Rehm. Münster: Ugarit-Verlag, pp. 71‑128, 2015

- ^ Porada, E., Hansen, D.P., Dunham, S., and Babcock, S., "The Chronology of Mesopotamia, ca. 7000-1600 B.C.", in Chronologies in Old World Archaeology I + II, ed. R. Ehrich, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 77–121, 1992

- ^ [19]Palmero Fernandez, Monica, "Shaping the goddess Inanna/Aštar: temple construction, gender and elites in early dynastic Mesopotamia (ca. 2600–2350 BC)", Dissertation, University of Reading, 2019

- ^ [20]Reichel, C., "Second regional workshop in Blaubeuren, February 5–9, 2009: scientific report", Technical report, University of Toronto, Toronto, 2009

- ^ [21] Pinhas Delougaz, "Pottery from the Diyala Region", Oriental Institute Publications 63, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1952, ISBN 0-226-14233-7

- ^ Painted Khafajeh jar at British Museum

- ^ Sharlach, Tonia, "Princely Employments in the Reign of Shulgi", Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1-68, 2022

- ^ Thomas, Ariane, "The Akkadian Royal Image: On a Seated Statue of Manishtushu", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 105, no. 1-2, pp. 86-117, 2015

- ^ Frayne, D. R., "The Sargonic and Guti Period", RIME 2. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1993

- ^ Frayne, Douglas, "Ur-Nammu E3/2.1.1". Ur III Period (2112-2004 BC), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 5-90, 1997

- ^ Gelb, I. J., "Prisoners of War in Early Mesopotamia", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 32, no. 1/2, pp. 70–98, 1973

- ^ [22] R. M. Whiting Jr., "Old Babylonian Letters from Tell Asmar", Assyriological Studies 22, Oriental Institute, 1987 ISBN 0-918986-47-8

- ^ Abi-matar Year Names at CDLI

- ^ Ebeling,E. and Meissner,B., "Reallexikon der Assyriologie (RIA-2), Berlin, 1938

- ^ Harris Rivkah, "The Archive of the Sin Temple in Khafajah (Tutub)", Journal of Cuneiform Studies, vol. 9 no. 2, pp. 31-55, 1955

- ^ Harris, Rivkah, "The Archive of the Sin Temple in Khafajah (Tutub)(Continued)", Journal of Cuneiform Studies 9.3, pp. 59-88, 1955

- ^ Harris, Rivkah, "The Archive of the Sin Temple in Khafajah (Tutub)(Conclusion)", Journal of Cuneiform Studies 9.4, pp. 91-120, 1955

- ^ S. Greengus, "Old Babylonian Tablets from Ishchali and Vicinity", PIHANS 44, Istanbul-Leiden, 1979 ISBN 978-90-6258-044-6

- ^ Viaggio, Salvo, "Old Babylonian Texts (Diyala Region) from the Hearst Museum of Anthropology, Berkeley", Dallo stirone al Tigri, dal tevere all’Eufrate. Studi in onore di Claudio Saporetti, pp. 377-390, 2009

- ^ J.J. Finkelstein, "The Antediluvian Kings: A University of California Tablet", JCS 17, pp. 39-51, 1963

- ^ D.A. Foxvog, "Texts and fragments 101-106”, JCS 28, pp. 101-106, 1976

Further reading

- Battini, Laura, "Un nom pour la divinité adorée dans le" Sin Temple" à Khafadjé", Akkadica 127, pp. 93-94, 2006

- Ch. P., "Les Fouilles de Khafaje", Revue Archéologique, vol. 11, pp. 90–90, 1938

- Ch. P., "Fouilles de Khafaje", Revue Archéologique, vol. 13, pp. 262–262, 1939

- [23]P. Delougaz, "Planoconvex Bricks and the Methods of their Employment", Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 7, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1933

- Edzard, D. O., "ITU-Tubki = Tutub", Archiv Für Orientforschung, vol. 20, pp. 152–152, 1963

- Evans, J., "Thinking through assemblages: donors and the Sin Temple at Khafajah", in Ancient Near Eastern Temple Inventories in the Third and Second Millennia BCE: Integrating Archaeological, Textual, and Visual Sources (Münchener Abhandlungen zum Alten Orient 4), Gladbeck, pp. 13-26, 2019

- Evans, Jean M., "Left Behind: Early Dynastic Temple Deposits in the Sin Temple at Khafajah", Votive Deposits in Early Dynastic Temples, Oriental and European Archaeology Volume 27, pp 101-109, 2023

- Evans, Jean M., "Defining the Sacred in the Houses at Khafajah", Archaeology from Every Angle: Papers in Honor of Richard L. Zettler, pp. 88-101, 2024

- Henri Frankfort, "The Oldest Stone Statuette Ever Found in Western Asia, and Other Relics of Ancient Sumerian Culture of a Period Probably before 3000 B.c.: Earliest Temple at Khafaje", The Illustrated London News, pp. 524-526 and col. pl. I, September 26 1936

- Henri Frankfort, "Two Iraq Sites over 5000 Years Old: Fresh Discoveries at Tell Asmar, Source Of First-known Sumerian Cult-Statues, and at Khafaje, Which Later Yielded Similar Types of Early Religious Sculpture", The Illustrated London News, pp. 726-32 and col. pl. I, September 14 1935

- Henri Frankfort, ""A Moon-God's Temple with Art Relics of about 3000 BC : New Discoveries at Khafaje, Mesopotamia", The Illustrated London News, pp. 840-841, November 13 1937

- Gibson, McGuire. "The Isin-Larsa Sin Temple at Khafajah Relocated", Archaeology from Every Angle: Papers in Honor of Richard L. Zettler, pp. 102-110, 2024

- Guerri, L., "Space and Ritual in Early Dynastic Mesopotamia: a Contextual Analysis of the Shrines of Tutub", OCNUS 16, pp. 131-146, 2008

- Henrickson, Elizabeth F., "Functional Analysis of Elite Residences in the Late Early Dynastic of the Diyala Region: House D and the Walled Quarter at Khafajah and the Palaces at Tell Asmar", Mesopotamia Torino 17, pp. 5-33, 1982

- Kempinski, A., "The Sin Temple at Khafaje and the En-Gedi Temple", Israel Exploration Journal, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 10–15, 1972

- Luce, Stephen B., and Elizabeth Pierce Blegen, "Archaeological News and Discussions", American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 310–45, 1939

- Margueron, Jean-Claude, "Notes d’archéologie et d’architecture orientales 16. De la strate à la couche architecturale : réexamen de la stratigraphie de Tuttub/KhafajéI - L’architecture civile", Syria, vol. 89, pp. 59–84, 2012

- [24]Margueron, Jean-Claude, "Notes d’archéologie et d’architecture orientales 17-De la strate à la «couche architecturale»: réexamen de la stratigraphie de Tuttub/Khafadjé", Syria. Archéologie, art et histoire 91, pp. 127-171, 2014

- Margueron, J. C., "Un centre administratif religieux dans l’espace urbain à Mari et à Khafadjé (fin DA et Agadé)", Akh Purattim 2, pp. 245-277, 2007

- Meijer, Diederik J.W., "The Khafaje Sin Temple Sequence: Social Divisions at Work?", in Of Pots and Plans: Papers on the Archaeology and History of Mesopotamia and Syria Presented to David Oates in Honour of His 75th Birthday, ed. L. al-Gailani Werr, J.Curtis, H.Martin,A.McMahon, J.Oates and J.Reade. London: NABU, pp. 218–26, 2002

- Pollock, S., "Ancient Mesopotamia: the eden that never was", Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999

- A. Skaist, "The Sale Contracts from Khafajah", in Bar-Ilan Studies in Assyriology (ed. J. Klein and A. Skaist; Ramat Gan), Bar-Ilan University Press, pp. 255–58 and 263, 1990

- [25]Speiser, Ephraim A., "Khafaje, 1937", The University Museum Bulletin 6, no. 6., pp. 14-18, 1937

External links

- Khafaje excavation objects at Penn Museum

- Plaque decorated with three registers of relief, showing banquet scene with musicians - ca. 2600 B.C at Oriental Institute

- Sumerian Temple Architecture in Early Mesopotamia. Rice University (OpenStax Project)

- Archival storage for Penn Museum excavation at Khafajah

Read

Read

AUTHORPÆDIA is hosted by Authorpædia Foundation, Inc. a U.S. non-profit organization.

AUTHORPÆDIA is hosted by Authorpædia Foundation, Inc. a U.S. non-profit organization.