Sophocles

Parmenides | |

|---|---|

Bust of Parmenides discovered at Velia, thought to have been partially modeled on a Metrodorus bust. | |

| Born | c. late 6th century BC |

| Died | c. 5th century BC |

| Philosophical work | |

| Era | Pre-Socratic philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Eleatic school |

| Main interests | Ontology, poetry, cosmology |

| Notable ideas | Monism, truth/opinion distinction |

Parmenides of Elea (/pɑːrˈmɛnɪdiːz ... ˈɛliə/; Ancient Greek: Παρμενίδης ὁ Ἐλεάτης; fl. late sixth or early fifth century BC) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Elea in Magna Graecia (Southern Italy).

Parmenides was born in the Greek colony of Elea to a wealthy and illustrious family.[a] The exact date of his birth is not known with certainty; on the one hand, according to the doxographer Diogenes Laërtius, Parmenides flourished in the period immediately preceding 500 BC,[b] which would place his year of birth around 540 BC; on the other hand, in the dialogue Parmenides Plato portrays him as visiting Athens at the age of 65, when Socrates was a young man, c. 450 BC,[c] which, if true, suggests a potential year of birth of c. 515 BC.[1] Parmenides is thought to have been in his prime (or "floruit") around 475 BC.[2]

The single known work by Parmenides is a philosophical poem in dactylic hexameter verse whose original title is unknown but which is often referred to as On Nature.[3] Only fragments of it survive, but the integrity of the poem is remarkably higher than what has come down to us from the works of almost all other pre-Socratic philosophers, and therefore classicists can reconstruct the philosophical doctrines with greater precision. In his poem, Parmenides prescribes two views of reality. The first, the Way of "Aletheia" or truth, describes how all reality is one, change is impossible, and existence is timeless and uniform. The second view, the way of "Doxa" or opinion, describes the world of appearances, in which one's sensory faculties lead to conceptions which are false and deceitful.

Parmenides has been considered the founder of ontology and has, through his influence on Plato, influenced the whole history of Western philosophy.[4] He is also considered to be the founder of the Eleatic school of philosophy, which also included Zeno of Elea and Melissus of Samos. Zeno's paradoxes of motion were developed to defend Parmenides's views. In contemporary philosophy, Parmenides's work has remained relevant in debates about the philosophy of time.

Biography

Parmenides was born in Elea to an aristocratic family.[5] Diogenes Laertius says that his father was Pires.[6] Laertius transmits two divergent sources regarding the teacher of the philosopher. One, dependent on Sotion, indicates that he was first a student of Xenophanes,[7] but did not follow him, and later became associated with a Pythagorean, Aminias, whom he preferred as his teacher. Another tradition, dependent on Theophrastus, indicates that he was a disciple of Anaximander.[8]

Chronology

Parmenides was one of the pre-Socratic philosophers.[9] As with all pre-Socratic philosophers, the little known about his life and work comes from writings and quotations by later philosophers.[10] Parmenides founded his school of thought in Elea.[9] His ideas were followed by Melissus of Samos and Zeno of Elea, with the latter being a close friend of Parmenides.[11]

Date of birth

All conjectures regarding Parmenides's date of birth are based on two ancient sources. One comes from Apollodorus and is transmitted to us by Diogenes Laertius: this source marks the Olympiad 69th (between 504 BC and 500 BC) as the moment of maturity, placing his birth 40 years earlier (544 BC – 540 BC).[12] The other is Plato, in his dialogue Parmenides. There Plato composes a situation in which Parmenides, 65, and Zeno, 40, travel to Athens to attend the Panathenaic Games. On that occasion they meet Socrates, who was still very young according to the Platonic text.[13]

The inaccuracy of the dating from Apollodorus is well known, who chooses the date of a historical event to make it coincide with the maturity (the floruit) of a philosopher, a maturity that he invariably reached at forty years of age. He tries to always match the maturity of a philosopher with the birth of his alleged disciple. In this case Apollodorus, according to Burnet, based his date of the foundation of Elea (540 BC) to chronologically locate the maturity of Xenophanes and thus the birth of his supposed disciple, Parmenides.[14] Knowing this, Burnet and later classicists like Cornford, Raven, Guthrie, and Schofield preferred to base the calculations on the Platonic dialogue. According to the latter, the fact that Plato adds so much detail regarding ages in his text is a sign that he writes with chronological precision. Plato says that Socrates was very young, and this is interpreted to mean that he was less than twenty years old. We know the year of Socrates's death (399 BC) and his age—he was about seventy years old—making the date of his birth 469 BC. The Panathenaic games were held every four years, and of those held during Socrates's youth (454, 450, 446), the most likely is that of 450 BC, when Socrates was nineteen years old. Thus, if at this meeting Parmenides was about sixty-five years old, his birth occurred around 515 BC.[14][15][16][17][18][19][20]

However, neither Raven nor Schofield, who follows the former, finds a dating based on a late Platonic dialogue entirely satisfactory. Other scholars directly prefer not to use the Platonic testimony and propose other dates. According to a scholar of the Platonic dialogues, R. Hirzel, Conrado Eggers Lan indicates that the historical has no value for Plato.[21] The fact that the meeting between Socrates and Parmenides is mentioned in the dialogues Theaetetus (183e) and Sophist (217c) only indicates that it is referring to the same fictional event, and this is possible because both the Theaetetus and the Sophist are considered after the Parmenides. In Soph. 217c the dialectic procedure of Socrates is attributed to Parmenides, which would confirm that this is nothing more than a reference to the fictitious dramatic situation of the dialogue.[22] Eggers Lan proposes a correction of the traditional date of the foundation of Elea. Based on Herodotus I, 163–167, which indicates that the Phocians, after defeating the Carthaginians in naval battle, founded Elea, and adding the reference to Thucydides I, 13, where it is indicated that such a battle occurred in the time of Cambyses II, the foundation of Elea can be placed between 530 BC and 522 BC So Parmenides could not have been born before 530 BC or after 520 BC, given that it predates Empedocles.[23] This last dating procedure is not infallible either, because it has been questioned that the fact that links the passages of Herodotus and Thucydides is the same.[24] Nestor Luis Cordero also rejects the chronology based on the Platonic text, and the historical reality of the encounter, in favor of the traditional date of Apollodorus. He follows the traditional datum of the founding of Elea in 545 BC, pointing to it not only as terminus post quem, but as a possible date of Parmenides's birth, from which he concludes that his parents were part of the founding contingent of the city and that he was a contemporary of Heraclitus.[20]

Timeline relative to other Presocratics

Parmenides would have been familiar with previous philosophers, such as the Milesians, as well as writers such as Homer and Hesiod.[5] He may have known a Pythagorean philosopher, Ameinias, who introduced him to philosophy.[5] Parmenides is sometimes described as beginning his study in the Milesian school under the tutelage of Anaximenes.[25] He may alternatively have been a student of Xenophanes.[25] Plato said that Parmenides traveled to Athens in 450 BCE, where he interacted with Socrates in the latter's youth.[5]

Rather than attempt to estimate Parmenides' chronology from ancient testimony, some scholars have turned directly to passages in his work to determine which other presocratic philosophers he may have influenced, and which philosophers may have been reacting to his doctrines, and working backwards to get a better estimate of the time in which he lived, including allusions to the doctrine of Anaximenes and the Pythagoreans (fragment B 8, verse 24, and frag. B 4), and also against Heraclitus (frag .B 6, vv.8–9), while Empedocles and Anaxagoras frequently refer to Parmenides. The Atomist doctrines of are also seen as reactions to the doctrines of the later Eleatics who followed Parmenides. However, the philosopher whose potential influence has provoked the most discussion is Heraclitus of Ephesus.(frag .B 6, vv.8–9) [26]

The potential references to Heraclitus in Parmenides work have been debated. Bernays's thesis[27] that Parmenides attacks Heraclitus, to which Diels, Kranz, Gomperz, Burnet and others adhered. However, at the same time Karl Reinhardt postulates his thesis of chronological inversion: Heraclitus would be posterior to Parmenides, so the passage could not have objected to the doctrine of that one.[28] Werner Jaeger followed suit on this point: he believes that the goddess's criticism is addressed to all mortals.[29] Although Heraclitus criticized other philosophers such as Xenophanes and Pythagoras, he does not include Parmenides in this list. Guthrie finds it surprising that Heraclitus would not have censured Parmenides if he had known him. His conclusion, however, does not arise from this consideration, but points out that, due to the importance of his thought, Parmenides splits the history of pre-Socratic philosophy in two, therefore his position with respect to other thinkers it is easy to determine. And, from this point of view, the philosophy of Heraclitus seems to him pre-Parmenidean, while those of Empedocles, Anaxagoras and Democritus are post-Parmenidean.[16] The evidence also suggests that Parmenides could not have written much after the death of Heraclitus.[30] Regardless of the acceptance or rejection of the chronological inversion, Guthrie also leans by this interpretation, but with important nuances: the goddess refers, effectively, to all mortals. However, Heraclitus could be exceptionally representative of the "judgmentless multitude" (ἄκριτα φῦλα v. 7), since the error that characterizes these is based on reliance on the eyes and ears (B 7, v. 4); , and Heraclitus preferred the visible to the audible (22 B 55). He adds that the Heraclitean assertions “wills and does not will” (22 B 32), “on diverging converges” (22 B 51), “on changing is at rest” (22 B 84a) “evidence of the quintessence of what Parmenides deplores here». In light of this accumulation of evidence, he points out, it is for this reason that what many have seen as the only unequivocal reference to Heraclitus (22 B 51) in verse 9 of fr. 6. “Where no isolated sentence provides conviction, the cumulative effect may be of vital importance.”[31]

Anecdotes

Parmenides worked in government, as was common for pre-Socratic philosophers.[5] Plutarch, Strabo and Diogenes—following the testimony of Speusippus—agree that Parmenides participated in the government of his city, organizing it and giving it a code of admirable laws.[32]

ΟΥΛΙΑΔΗΣ ΦΥΣΙΚΟΣ

Archaeological discovery

In 1969, the plinth of a statue dated to the 1st century AD was excavated in Velia. On the plinth were four words: ΠΑ[Ρ]ΜΕΝΕΙΔΗΣ ΠΥΡΗΤΟΣ ΟΥΛΙΑΔΗΣ ΦΥΣΙΚΟΣ.[33] The first two clearly read "Parmenides, son of Pires." The fourth word φυσικός (fysikós, "physicist") was commonly used to designate philosophers who devoted themselves to the observation of nature. On the other hand, there is no agreement on the meaning of the third (οὐλιάδης, ouliadēs): it can simply mean "a native of Elea" (the name "Velia" is in Greek Οὐέλια),[34] or "belonging to the Οὐλιος" (Ulios), that is, to a medical school (the patron of which was Apollo Ulius).[35] If this last hypothesis were true, then Parmenides would be, in addition to being a legislator, a doctor.[36] The hypothesis is reinforced by the ideas contained in fragment 18 of his poem, which contains anatomical and physiological observations.[37] However, other specialists believe that the only certainty we can extract from the discovery is that of the social importance of Parmenides in the life of his city, already indicated by the testimonies that indicate his activity as a legislator.[38]

Visit to Athens

Plato, in his dialogue Parmenides, relates that, accompanied by his disciple Zeno of Elea, Parmenides visited Athens when he was approximately sixty-five years old and that, on that occasion, Socrates, then a young man, conversed with him.[39] Athenaeus of Naucratis had noted that, although the ages make a dialogue between Parmenides and Socrates hardly possible, the fact that Parmenides has sustained arguments similar to those sustained in the Platonic dialogue is something that seems impossible.[40] Most modern classicists consider the visit to Athens and the meeting and conversation with Socrates to be fictitious. Allusions to this visit in other Platonic works are only references to the same fictitious dialogue and not to a historical fact.[41]

Philosophy

Parmenides depicted his philosophy as a divine truth,[42] and rejected the evidence of the senses, believing that truth could only be found through reason.[43] However, he considered both the divine and mortal understandings worth learning, as mortal understandings can still carry meaning.[42]

Ontology

Parmenides rejected the existence of Nonbeing, as something cannot be nothing. He defined all things that can be thought or spoken of as Being.[44] Only the path of Being can be followed, because Nonbeing can not be thought or spoken about. To believe in the existence of both Being and Nonbeing is self-contradictory and makes knowledge impossible.[45] His concept of eternal Being was of one that is without regard to time. As change cannot occur within Being, there are no intervals by which time can be measured.[44] Being is consistent in its form throughout its existence, as the only alternative to its state of being is not being. It is bound by its own form.[44] If Being had come from Nonbeing, then it would have no reason or cause to come into existence as Being. Being must be eternal, as its origin would either be from Nonbeing, which cannot exist, or it would be from Being, which means it would have always existed.[44] Being exists infinitely and is indivisible, as any space not occupied by being would be occupied by Nonbeing, which cannot exist. Being cannot move, as this would require there to be space that it does not already occupy.[44] Parmenides rejected the existence of the Void, as it would necessarily be made of Nonbeing, which cannot exist.[44]

Epistemology

As mortals think through their senses, Parmenides held that it is impossible for them to understand Being in its true form without distortion.[46] By naming each concept, humans have distorted the uniform nature of Being and created concepts of things that are neither consistent Being nor Nonbeing.[46] It is this simultaneous belief that forms the opinions of men.[46] Being holds the same properties as and is indistinguishable from the concept of truth, as it is self-contained, unchanging, and eternal.[47] Being is perceived in the mind, not through the senses. To apprehend something means that it must be something and not nothing and is therefore Being. Perceiving in the mind is distinct from thinking about something, as thinking pertains to specific objects that would divide Being.[48]

Cosmology

Parmenides developed a system defined by opposites, based on light and dark.[46] Mortal perception of the world involves the shifting light and dark within a person, which creates subjective mortal opinions that can differ between individuals. This was the first philosophical model of how sensory perception relates to mental understanding.[49] From the perspective of mortal opinions, each instance of opposites—such as hot and cold or male and female—are derived from the understanding of light and dark as distinct entities.[46] Life and death are a shifting of one's soul from light to dark.[49] In the mortal understanding, the exchange between light and dark is guided by a supreme power and blends the two to create different phenomena.[46] The supreme power, personified by the Goddess, exists in the center of the universe.[49] The existence of light and dark implies that Being and Nonbeing exist simultaneously. It is this contradiction that prevents mortals from understanding the true nature of Being.[46] These mortal opinions allow the perception of time and change even though they do not exist under a divine understanding.[49]

On Nature

Since antiquity, it has been believed Parmenides wrote only one work,[d] later titled On Nature.,[e] a didactic poem written in dactylic hexameterverse. The language in which it was written is archaic, the same format in which the epic was expressed, the Homeric dialect and . This form has several uses: it facilitates the mnemonics and recitation of the poem;[50] allows games of poetic form, such as chiastic structure[51] and the Ritournelkomposition.

Approximately 160 verses remain today from an original total that was probably near 800.[4] The poem was originally divided into three parts: an introductory proem that contains an allegorical narrative which explains the purpose of the work, a former section known as "The Way of Truth" (aletheia, ἀλήθεια), and a latter section known as "The Way of Appearance/Opinion" (doxa, δόξα). Despite the poem's fragmentary nature, the general plan of both the proem and the first part, "The Way of Truth", have been ascertained by modern scholars, thanks to large excerpts made by Sextus Empiricus[f] and Simplicius of Cilicia.[g][4] Unfortunately, the second part, "The Way of Opinion", which is supposed to have been much longer than the first, only survives in small fragments and prose paraphrases.[4]

Proem

The introductory proem describes the narrator's journey to receive a revelation from an unnamed goddess on the nature of reality.[52] It is composed from a rich symbology, which draws mainly from the epic tradition (both Homer and Hesiod), but also from Orphic symbology and other legends, and narrates an experience of a mystical-religious nature,[53][54][55][56] to which scholars have drawn comparison to varius mythological figures, including Etalides (Pherecydes, fragment 8 DK), Aristeas,[h] Hermothymus[i] and Epimenides.[j][54] The latter ran into the goddesses Truth and Justice while his body was sleeping, which is very close to the story of the proem.[54] The narrative of the poet's journey includes a variety of allegorical symbols, such as a speeding chariot with glowing axles, horses, the House of Night, Gates of the paths of Night and Day, and maidens who are "the daughters of the Sun"[57] who escort the poet from the ordinary daytime world to a strange destination, outside our human paths.[58] The allegorical themes in the poem have attracted a variety of different interpretations, including comparisons to Homer and Hesiod, and attempts to relate the journey towards either illumination or darkness, but there is little scholarly consensus about any interpretation, and the surviving evidence from the poem itself, as well as any other literary use of allegory from the same time period, may be too sparse to ever determine any of the intended symbolism with certainty.[52] The remainder of the work is then presented as the spoken revelation of the goddess without any accompanying narrative.[52]

The proem, begins with the description of a trip in a two-wheeled chariot (v. 7), pulled by a pair of mares, described as πολύφραστοι (polýphrastoi, v. 4), "attentive" or "knowledgeable". The image recalls the divine steeds of Achilles, sometimes even endowed with a voice.[59] Pindar also gives us a similar image of draft beasts "leading" along a "pure path" or "luminous"[60][61] There are so many common elements between the compositions that Bowra considers that either Pindar's mimics Parmenides's—it is later, from 468 BC—, or, what he considers more likely, that they have a common source from which they are both influenced.[62] Everything seems to suggest that the chariot is directed by superior powers, and we must rule out, as Jaeger says,[63] the platonizing interpretation of Sextus Empiricus, inspired by the myth of the "winged chariot" narrated in the Phaedrus (246 d 3 – 248 d), in which the chariot symbolizes the human soul. Surely the composition has a closer relationship with the myth of the death of Phaethon, since both this and the charioteers of this Parmenidean chariot are children of the Sun, and the path that is traveled is that of Night and Day (v. 11). It is the same "solar chariot."[64]

This path leads from the “dwelling of Night” to the light (vv. 9–10). In verse 11 it is said that the way is "of Night and Day." Hesiod had spoken of the «house of Night» in Theogony,[65] house in which both Night and Day dwell, only that in an alternate way, for never does the mansion accommodate both at the same time. The ancient view of the alternation of Night and Day can be characterized as a transit performed by both along the same path, but in ever different positions. The path of Night and Day is, therefore, a unique path. Hesiod geographically locates the abode of Night at the center of the Earth, in the immediate vicinity of Tartarus. Instead, Parmenides situates his scene, according to the material of the opening of the gates (they are "ethereal," v. 13), in the sky, like the gates of Mount Olympus, which Apollonius of Rhodes describes as ethereal and situated, of course, in the sky.[66] Following Sextus Empiricus, some scholars have seen this as the experience of a transition from Night to Light means the transit of the ignorance to knowledge,[54] while others dispute this, because the sage begins his journey in a flash of light, as is typical of one who "knows".[56] It is certain that the author's intention is to give his work the character of a divine revelation, since the content is placed in the mouth of the goddess, analogous to the epic muse. And it is a revelation not available to ordinary men.[67][54] that represents the abandonment of the world of everyday experience, where night and day alternate, a world replaced by a path of transcendent knowledge.[56] Werner Jaeger understood this path as a way of salvation that Parmenides would have heard about in the mystery religions, a straight path that leads to knowledge.[67]

The path on which he is led is interrupted by an immense stone gate, whose guardian is Dike. The daughters of the Sun persuade her, and she opens the door for the chariot to pass through (vv. 11–21). As in Homer, the gates of Olympus are guarded by the Horae, daughters of Zeus and Themis,[68] the gate of the Parmenidean poem is curated by Dike, one of them. The Heliades persuade, with soft words, to the goddess to run the bolt, and she finally opens the door. Access to the truth is not, however, the merit of the "man who knows", since he is dragged by superior forces, the mares and the Heliades, his passage through the formidable barrier described in the poem is allowed by Dike and his journey he has from the first been in favor with Themis. Transit is in accordance with law.[54] In Parmenides' poem, Dike is adjectiveized as πολύποινος (polýpoinos, "rich in punishments" or "avenger," v. 14). The expression Δίκη πολύποινος (Dike polýpoinos) is present in an Orphic poem (fr. 158 Kern). This, plus the fact that Dike possesses the keys "of alternate uses" or "of double use" (ἀμοιβἤ, amoibê, v. 14), another possible ritual element, made one think of a close relationship between Parmenides and the Orphic cults, so abundant in southern Italy.[69] The turn εἰδότα φῶτα (eidóta phōta, "man who knows"), opposed to mortals and their ignorance, does no more than reinforce this link (see Orpheus, fr. 233 Kern).[70]

Once the chariot passes the threshold, the “knowing man” is received by a goddess—whose identity is not revealed—with a typical gesture of welcome. Her speech, beginning at line 24, is the content of the rest of the poem. The narrator is greeted by a goddess, whose speech, Most scholars agree in showing the very close relationship between this nameless goddess (θεά, theá) and the Muses of the epic: Homer invokes her with the same word in the first verse from the Iliad: «Sing, goddess...»; the divinity is the one she sings about, by virtue of the fact that she knows "all things" (Il. II, 485). The Muses of Hesiod even specify something similar to what the Parmenidean goddess said about true and apparent speech: «We know how to tell many lies with appearances of truth; and we know, when we want, to proclaim the truth» (Thegony, vv. 27ff).[56][71] She tells him, in the first place, that he has not been sent by an evil destiny, but by law and justice (vv. 26-28). It is not, says the goddess, this fate that has led the protagonist along the route of Night and Day: the author seems to oppose here the fate of the "man who knows" and that of Phaethon, whose disastrous journey in the chariot of the Sol only ended with his death.[64] "Moira" belongs to the set of divinities related to divine justice, such as Themis and Dike, who are the ones that have allowed the transit of a mortal through the route of the Sun. Themis personifies customary law;[72][73] in the epic, it is the set of norms of social behavior , not formulated, but that no mortal can ignore. The good disposition shown by the goddesses associated with law means that the trip has been permitted or approved by the divinity.[74][75] By virtue of this, he continues, it is necessary that he know all things, both "the unshakable heart of persuasive truth" and "the opinions of mortals", because, although in these "there is no true conviction", without yet they have enjoyed prestige (vv. 28–32). It is necessary for the narrator to also know the opinions of mortals (vv. 31–32) because what is a matter of opinion (τὰ δοκοῦντα, tà dokoûnta) is all-encompassing, which means that opinions are all that mortals could know without considering the revelation of the Parmenidean goddess. They have necessarily enjoyed prestige and that is why they must be known. The passage is closely related to the end of Fragment 8, v. 60ss, where the goddess says that she expounds the probable discourse on the cosmic order so that no mortal opinion outweighs the receiver of the revelation.[76]

The Way of Truth

In the Way of Truth, an estimated 90% of which has survived,[4] Parmenides distinguishes between the unity of nature and its variety, insisting in the Way of Truth upon the reality of its unity, which is therefore the object of knowledge, and upon the unreality of its variety, which is therefore the object, not of knowledge, but of opinion.[77]

B2

Proclus preserves, in his commentary on Timaeus I 345, 18–20, two lines of Parmenides's poem, which together with six lines transmitted by Simplicius, in his commentary on Aristotle's Physics, 116, 28–32–117, 1, form fragment 2 (28 B 2). There the goddess speaks of two "paths of inquiry that there are for thinking (nous)". The first is named as follows: "which is, and also cannot be that it is not" (v. 3); the second: "which is not, and also, must not be" (v. 5). The first way is "of persuasion", which "accompanies the truth" (v. 4), while the second is "completely inscrutable" or "impracticable", since "what is not" cannot be known, nor expressed (vv. 6–8).

B3

Fragment B3[78] is just a part of dactylic verse:Ancient Greek: ...τὸ γὰρ αὐτὸ νοεῖν ἐστίν τε καὶ εἴναι. Following the order of the words and the literal meaning of each word, it could be translated (and understood) as follows: "the same thing is to think and to be". Plotinus, who cites the text, believes he finds in it support for his idea of the identification of being with thinking, a fundamental idea of Neoplatonism. However, some modern scholars[79][80] have interpreted it as closer to "the same is to be thought and to be" For Jaeger, the semantic value of νοεῖν is not identical to that used later by Plato, who opposes it to sensible perception. Rather this is an "awareness" of an object in what it is. The νοεῖν is not really νοεῖν if it does not know the real.[81] Guthrie adds that the action of the verb cannot suggest the image of something that does not exist. In Homer it has a similar meaning to "see" (Il XV, 422), rather it is the act by which someone receives the full meaning of a situation (Il III, 396), not through a process of reasoning, but a sudden illumination. Subsequently, νοῦς (noûs) is conceived as a faculty that cannot be subject to error, as Aristotle will later say in Posterior Analytics, 100b5.[82]

B6

In fragment B6, nine verses preserved by Simplicius,[83] Parminides continues to speak of the ways of thought. The first three verses argue against the second way, presented in B 2, v. 5: Postulates that it is necessary to think and say that "what is" is, since it is possible that it is, while it is impossible for "nothing" to be. And this is the reason why the goddess removes the "man who knows" from the second way. Immediately, the goddess speaks of a third path that must be left aside: the one in which mortals wander, wandering since they are dragged by a wavering mind, which considers that being and not being are the same, and at the same time it is not the same. himself (vv. 4–9). It is the way of opinion, already presented in B 1, v. 30. Fragment 6 has been interpreted by some philologists as a reference to the thought of Heraclitus. There it speaks of the "two-faced" (δίκρανοι v. 5), those who believe that "being and not being is the same and not the same" (vv. 8–9). This appears to be a criticism of the Heraclitean doctrine of the unity of opposites.[k] Verse 9 "from all things there is a retrograde way" (πἄντων δὲ παλίντροπός ἐστι κέλευθος), seems to point directly to an idea present in a fragment of Heraclitus: (22 B 60): "the up way and below is one and the same»; and to the same letter of another fragment (22 B 51): "...harmony of that which turns back» (παλίντροπος ἁρμονίη).[84]

In the Fragment 2, Parmenides presents two[l] paths of inquiry, δίζησις (dizēsis , v. 2), mutually exclusive: one must be followed and the other is inscrutable. In fragment 6, however, a third path appears from which one must turn away (v. 4ff). The characterization of these paths has initiated a discussion about the amount of paths presented and on the nature of these. Werner Jaeger says that throughout the writing the meaning of «path» is that of «salvation path». That is why he compares this disjunction of the paths with those of the religious symbolism of later Pythagoreanism, which presented a straight path and a path of error, in the sense of morally good and bad paths. The choice of one of them is made by man as a moral agent. He also offers as background a passage from Works and Days (286ff) where Hesiod presents a flat path, that of wickedness, and a steep one, that of virtue. Either way, he accepts that there is in the poem a transfer from religious symbolism to intellectual processes. In this sense, compared to the two exclusionary paths of fragment 2 (he calls them that of "being" and that of "not being"), the third path of fragment 6 is not a different path, but rather an inadmissible combination of these two, followed by those who have not noticed their mutual exclusion.[85] Raven points out that the third way is that of mortals, who wander "two-headed" (δίκρανοι, díkranoi), because they combine opposites, as Simplicius had noted.[56] Schofield argues that this third way had not been shown in fr. 2, since there were coherent alternatives between which a researcher must decide, while this is a path that anyone who does not make this decision and does not use his critical faculties finds himself on (fr. 6, vv. 6 –7), following both contradictory paths at the same time.[56] For Guthrie there are effectively three ways, the second is discarded and the third, which arises from the use of the senses and habit, includes the belief that "things that are not are" and "that being and not being are the same and not the same” (fr. 6, v. 8).

B7

Another fragment, B7[86] the next seven verses follow this reflection and concludes it: there is no way to prove "what is what is not" (v. 1). For this reason, the goddess indicates that it is necessary to deviate from this path of inquiry, going even against custom, which leads to the "inattentive gaze" and the "rumbling ear and the tongue", that is, to the senses (vv. 2 -4). Instead, she recommends following her controversial argument with reason (vv. 5–6). Part of line 6, and what remains of line 7, connects the theme of the paths of inquiry with fragment A8: only the path discourse dealing with 'what is' remains.

B8.1-4: Signs about "What is"

In the longest surviving fragment, B8,[87] the goddess(v. 1-4) describes a series of "signs" about "what is": “unbegotten and indestructible” (ἀγένητον καὶ ἀνώλεθρον, v. 5-21), “whole and unique” (οὔλοε μοέον, v. 22-25), “immovable” (ἀτρεμής, v. 26-33) and “perfect” (τελεῖον, v. 42-49), which are along the path and which come to be a set of attributes of "what is".

The program itself, however, concludes with an inexplicable "endless (in time)" (ἠδ᾽ ἀτέλεστον) which would contradict verse 5, which indicates that "what is" is foreign to both the past and the future.[88] Owen offers the following conjecture as a solution to this difficulty: the reading is a copyist's error, seduced by the reiteration of negative prefixes in the poem (ἀγένητον... ἀνώλεθρον... ἀτρεμές) and by the influence of a Homeric cliché,.[89] and should read ἠδὲ τελεῖον, "perfect." With this amendment a complete correspondence between the program and the arguments is achieved.[90] Guthrie nevertheless decides on the original reading (the only one attested in the manuscripts) and rejects Owen's emendation, understanding this "infinity" in a new sense, different from the Homeric use of the term, which precisely means "incomplete", "unfinished" and that contradicts the ideas presented in the poem about the attributes of perfection of the entity.[91] Raven follows the reading of Diels,[92] but Schofield follows Owen's conjecture.[56]

B8.5-21 "What is" cannot be begotten or destroyed

From verse 5 to 21 a lengthy argument is developed against generation and corruption. Verse 5 posits On the other hand, if nothing can be understood or said about "what is not", then there is no possibility of finding out from where it would have been generated, nor for what reason it would have been generated "before" or "after", emerging from nothing. (verses 6–10). It is necessary that it be completely, or that it not be at all, therefore it cannot be admitted that from what is not something arises that exists together with "what is" (vv. 11-12). Generation and corruption are prohibited by Justice, by virtue of a decision: "it is or it is not", and it has been decided to abandon this last path as inscrutable, and follow the first, the only true path (vv. 14-18) . Nor can the entity, being, be born. And if he was born, he is not. Nor can it be if it is going to be. Therefore the generation is extinct, and perishing cannot be known (vv. 19–21). The first sign that the goddess deals with is the one related to the entity's relationship with time, the generation and corruption. In verse 5 of fragment 8 she affirms that the entity was not in the past nor should it be in the future, but is entirely now (νῦν ἔστι ὁμοῦ πᾶν). The past and the future have no meaning for the entity, it is in a perpetual present, without temporal distinction of any kind.[56] What follows (vv. 6–11) is the argument against the birth or generation of what is. The first words (“one”, ἕν, and “continuous”, συνεχές) advance the content of another argument located later on unity and continuity (vv. 22–25). From there, she wonders what genesis would you look for? It denies the possibility that "what is" arises from "what is not", since one cannot think or say “what is not” (vv. 7–9) there would be no need for something "that is" to emerge from "what is not" (vv. 9-10). Schofield has interpreted Parmenides here as 'appealing to the principle of sufficient reason. He supposes that everything that comes to be must contain in itself a principle of development ("necessity", χρέος) sufficient to explain its generation. But if something does not exist, how can it contain such a principle?»[56] The meaning of lines 12–13 is ambiguous, due to the use of a pronoun (αὐτό) that can be interpreted as referring to the object that has been spoken of for nine lines, “what is”, or as referring to the subject of the sentence in which it appears: «what is not». The first alternative and the final meaning of the sentence would be: from "what is not" something cannot arise that becomes together with "what is", that is, something other than "what is". This sentence would have the same content as that of verse 36–37: "nothing can exist apart from what is." This interpretation has been followed by Raven,[56] but rejected by Guthrie, because it introduces, according to him, elements alien to the argument about generation and corruption that dominates the section as a whole. He interprets as follows: 'what is not' can only be generated from 'what is not'.[91] In this sense, it would be one of the first versions of the phrase ex nihilo nihil fit, "from nothing nothing arises", which is also an axiom already accepted by the "philosophers of nature', as Aristotle observes (Physics 187a34).[93] Throughout the fragment there is no direct argument against corruption, but it can be deduced from postulating as exclusive the "is" and the "is not" (v. 16), and rejecting the "is not" (vv. 17– 18): perishing involves accepting that "what is" might "not be" in the future. Likewise, the generation implies that "what is" has not been in the past (vv. 19–20).[56] From the point of view of the history of thought, Parmenides achieves a true intellectual achievement by distinguishing here the enduring from the eternal. What is enduring is in time: it is the same now as it was thousands of years ago, or in the future. This is how the ancients thought of the perdurability of the cosmos or physical universe, as distinct from the eternity of what it is (Plato, Timaeus 38c2, 37e–38a). While eternity was posited by the Ionians—Anaximander said that their ἄπειρον was immortal, eternal, and ageless—they had also thought that their respective principles were starting points of the world. Parmenides, on the other hand, shows that if it is accepted that what is is eternal, it must be one, and cannot be the beginning of a multiform world, of an order of plural elements. Much less of a world subject to becoming, as Aristotle also expresses as the opinion of the ancient philosophers: "what is does not become, because it already is, and nothing could come to be from what it is not" ('Physics' ' 191a30).[94]

B8.22-25: "What is" is whole

From verse 22 to 25, the poem deals with the condition of integrity of "what is". No parts can be distinguished in it, since it is uniform: there is no more and less in it, it is simply full of "what is", and is alone with itself. In this passage Parmenides denies two ideas present in the cosmogonies and in the speculations of thinkers before him: the gradation of being and the emptiness. Anaximenes had spoken of the condensation and rarefaction of his principle (13 A 7), actions that, in addition to generating movement (which has already been rejected by Parmenides), supposes assuming certain degrees of density, but strictly adhering to "what is" prevents this type of gradual differences of existence.[56] In this cosmogony, for the cosmos to emerge from the beginning, it must have some unevenness of texture, lack of cohesion or balance.[95] It also prevents differentiating things according to their nature, as Heraclitus had intended (22 B 1). Guthrie rejects the reference to Anaximenes exposed above.[96] But above all he seems to reject here the idea of emptiness, which the Pythagoreans considered as necessary to separate the units, physical and arithmetical at the same time, from which the world was composed.[56][95] Apart from these historical considerations, the passage has generated some controversy regarding the dimension that Parmenides mentioned when referring to continuity. Owen interpreted this continuity of being to refer exclusively to time,[97] but Guthrie understands that the beginning of the passage ("neither differentiable is...", οὐδε διαρετόν ἐστιν, v. 22) introduces a new and independent argument from the previous one, and that the predicate of the homogeneous ("is a uniform whole", πᾶν ἔστιν ὁμοῖον, same verse), even based on what is said in verse 11: "it must be completely, or not be at all", that is, in a part of the argument against the generation, has a further consequence: in the present continuous of "what is," he exists fully, and not in varying degrees.[95] Schofield indicates that Parmenides thinks of a continuity of what is, in whatever dimension he occupies, and this quote also refers to a temporal continuity.[56]

B8.26-33 "What is" is motionless

Immobility is treated from verses 26 to 33. This is understood first as a denial of transit, as generation and corruption, which have already been repelled by true conviction (vv. 26-28). Then he says that "what is" remains in its place, in itself and by itself, compelled by necessity, which holds it "with strong ties" (vv. 29-31). An additional reason for his immobility is that he lacks nothing (v. 32), since, lacking something, he would lack everything (v. 33).

B8.42-49: "What is" is perfect

In verse 42,[n] the discourse deals with the attribute of perfection: "what is" is similar to the mass of a well-rounded ball, it cannot be less somewhere and more somewhere else, all of it is equidistant from the center (vv. 43–44) Remaining identical to itself, it fulfills its own limits.(vv. 45–49).

Parmenides (v. 43) describes what is as a "σφαίρης" (sphaires), which in classical Greek means "that which has a spherical shape" which in antiquity led some commentators to claim that Parmenides believed in a "spherical universe"[98] or a "spherical god"[99] or even a statement about the roundness of the Earth.[100] This interpretation has a parallel with the later geometrical model of the universe in Plato's Timaeus, where the Demiurge makes the world spherical, because the sphere is that figure that contains all the others, the most perfect and similar to itself.[101] However, both Plato and Parmenides distinguished between the "sensible" world and the "intelligible" world, and, considering the world of the senses unreal, so it is unlikely either of them was intending to make a statement about the shape of the material universe.[102][56] Additionally, in the Homeric language used by Parmenides, σφαίρα is nothing more than a ball, like the one they played with Nausicaa and her female servants upon reaching them Odysseus.[103][104][105] The Parmenidean entity could be thought of as a sphere, but it is ultimately neither spherical nor spatial, taking into account that it is a reality not perceptible by the senses, it is timeless, it does not change its quality and it is immobile. The "boundaries" are not spatial, but a sign of invariance.[106] The limits are also not temporary, since this would involve accepting generation and corruption. The comparison with the sphere is required because it represents a reality in which every point is the same distance from the center, and therefore no point is more "true" than another. It is an image of the continuity and uniformity of the entity.[104][107]

Already Plato had understood that the Eleatics denied movement because the One lacked a place where it could move;[108] this idea of the absence of a void was first expressed by Melissus of Samos.[109] In this attribute of what is, the idea of limit (πεῖρας) plays a fundamental role. It is associated with bonds or chains, such as those with which Odysseus was tied by his companions in Od. XII, 179. These uses maintain the idea of a certain deprivation of spatial mobility. The idea of limit is also related to "what is established by the gods." Because, in the poem, one of the arguments in favor of immobility is the fact that “what is” cannot be incomplete, this would be “illicit”: οὐκ ἀτελεύτητον τό ἐόν θἔμις εἶναι (v. 32). The term ἀτελεύτητον is used in Il., I, 527: there Zeus says that what he assents to «does not remain unfulfilled». This is equivalent to Parmenides' "is perfect" (τετελεσμένον ἔστι v. 42).[110] The use of «limit» linked to the sense of «perfection» or «consummation» is also attested in Il. XVIII, 501 and Od V, 289.[111] The "limit" is, moreover, one of the fundamental principles of the Pythagoreans, and heads the left column of their Table of Opposites (58 B 4–5 = Met. 986a23), column in which were also, among others, the One, the Still and the Good.[56]

The Way of Opinion

In the significantly longer, but far worse preserved latter section of the poem, Way of Opinion, Parmenides propounds a theory of the world of appearance and its development, pointing out, however, that, in accordance with the principles already laid down, these cosmological speculations do not pretend to anything more than mere appearance. The structure of the cosmos is a fundamental binary principle that governs the manifestations of all the particulars: "the Aether fire of flame" (B 8.56), which is gentle, mild, soft, thin and clear, and self-identical, and the other is "ignorant night", body thick and heavy.[112][o] Cosmology originally comprised the greater part of his poem, explaining the world's origins and operations.[p] Some idea of the sphericity of the Earth also seems to have been known to Parmenides.[4][q]

B8.50-52, 34-41: The Fates

The end of fragment 8, preserved by Simplicius, corresponds to an initial characterization of the opinion pathway. The goddess indicates that with the above considerations trustworthy speech ends, and a "deceitful order of words" begins: that of the opinions of mortals (vv. 50-52). The content of lines 34 to 36[r] is deeply related to fragment B3: it postulates that what must be intellectively known is that by which intellection is: intellective knowing itself (noein) is revealed in "what is"; in fact, there is nothing more than "what is" Lines 34 to 36 and the first half of 37 are linked to the verse that constitutes fragment 3 and its meaning. And this is revealed by the parallelism of the construction νοεῖν ἔστιν (fr. 3) / ἔστιν νοεῖν (fr.8, v. 34). The Moirai keeps the entity whole and motionless (vv. 37–38); This forces us to think that everything that mortals have thought to be true is nothing more than a network of mere names that designate changes: to be born and to perish, to be and not to be, to vary in place and color (vv. 39–41). Guthrie notes that, in this passage, Parmenides elevates his diction to epic and religious solemnity, and gives an important role to the divinities Moiras and Ananke. The use of the word refers to the scene of Hector who, chained to his Destiny, has remained outside the walls of Troy ( Il . XXII, 1– 6). Guthrie understands that Parmenides' reason for holding the idea of immobility is that "what is" is continuous and indistinguishable in parts, which prevents it from moving as a whole or changing internally.[113]

The first line is interpretable in multiple ways.[114] First of all, the interpretation depends on the determination of the subject. Thus, Guthrie, following Zeller, Fränkel and Kranz, understands that νοῆμα is linked to the verb ἔστι, so that the subject would be «what what can be thought. The meaning of the first line would be: "What can be thought and the thought that 'is' are the same."[114] On the other hand, Diels, Von Fritz and Vlastos, among others, have thought that the subject is the infinitive Mood νοεῖν: that is “thinking”. Diels and Von Fritz,[115] following the interpretation of Simplicius, they have also understood that οὐνεκέν has a causal or consecutive value (Guthrie gives it the value of a mere conjunction), so the meaning of this verse would be: "Thinking is the same as that which is the cause of thinking." Ultimately, there are two possible interpretations: 1) the one that maintains that what is said here is that thinking and being have a relationship of identity.[116] 2) that the idea of fragment 3 is being repeated here. and that of verse 2 of fragment 2: That is, that thought only reveals itself and realizes itself in "what is".[117] Vlastos argues that the thought he knows can hardly be denied existence. But if it exists, it must be part of what it is. But what is has no parts, but is homogeneous. Then thinking can only be the totality of what it is. What it is is intelligence.[116] In this dispute, Cornford rightly points out that nowhere in the poem does Parmenides indicate that his One thinks, and that no Greek of his day would have held that 'if A exists, A thinks'. Rather he held that thought cannot exist without something existing.[118] Owen points out that Plato, in Sophist 248d–249a, hinted that Parmenides was not faced with the problem of whether the real possesses life, soul, and understanding.[119] The only sure thing is that there is a close relationship between what is and knowing, which are faced by the actions of being born and perishing, being and not being, changing place or color, which strictly speaking "are mere names" which mortals have agreed to assign to things that are unreal, and then persuaded themselves of their reality. The whole of these names is the content of the way of opinion.[56][120]

B8.53-64: Primordial Elements

In fragment 8, the elements that make up the opposition to which the world of appearance can be reduced have been presented: φλογός αἰθέριον πῦρ (phlogós aitherion pŷr, «ethereal fire of the flame», v. 56) and νύξ (nýx, «night», v. 59). Mortals have distinguished two forms, πῦρ (pŷr, "fire", v. 56) and νῦξ (nŷx, "night", v. 59). In relation to these opposites, the goddess says that "the mortals have erred", however line 54, which contains the reason for the error, presents three possibilities of translation. She literally says τῶν μίαν οὐ χρεών ἐστιv. These three interpretations exhaust the possibilities of the text, and all have been supported by specialists.

These, the mortals, have given names to two forms, with which they have gone astray, because it is only lawful to name one (v. 54). They assigned these forms different properties, and considered them opposite: on the one hand, fire, soft, light and homogeneous; on the other, the night, compact and heavy (vv. 55–59). The goddess declares this speech no longer true, but plausible in appearance, and communicates it so that, in the order of opinions, the sage is not surpassed either (vv. 60-61). Simplicius, pointed out that in this passage Parmenides transits from the objects of reason to sensible objects.[121] The goddess calls the content of this second part βροτῶν δόξας (brotôn dóxas, "opinions of mortals", v. 51). Keep in mind that δόξα means what seems real or is presented to the senses; what seems true constituting the beliefs of all men; and what seems right to man.[77] The speech does not pretend to be "true", since everything that could be said reliably has already been said. On the contrary, what he will present will be a κόσμος ἀπατηλός (kósmos apatēlós, «deceitful order»), since he presents beliefs as if they were presided over by an order.[56]

- The first interpretation consists in indicating that the error is to name the two forms, since only one must be named.

- Aristotle understood that, once Parmenides considered that outside of what is nothing there is, he was forced to take phenomena into account, and to explain them he postulated opposites: cold and hot, or fire and earth , and that hot is «what is» and cold «what is not» (Met I 5, 986b30 = A 24).

- Zeller translated the passage as "one of which should not be named". This means that the other exists and can be named.[122]

- Burnet followed this interpretation, adding that these forms can be identified with the Pythagorean principles of limit and limitlessness.[123]

- Schofield reflects this interpretation by translating the passage "of which they must not necessarily name more than one".[56]

- In contrast to this, another interpretation indicates that none of the forms should be named.

- The most accepted interpretation indicates that the error is not to consider these two forms at the same time, but to name only one.

- Simplicius, who transmits the quote, thought that the error consists in not naming both contraries in the description of the physical world. The sentence would then say "of which it is not proper to name a single one." Modern philology has followed this interpretation in some of its exponents, such as Coxon and John Raven.

- The first indicates that Parmenides knows that starting from a single form necessarily leads to uniformity, since only one element can originate itself. He begins in two ways, deliberately, in order to explain not only the multiplicity, but the contradiction in the world.[124]

Fränkel, even deciding on an intertextual interpretation that corresponds to the first exposed here: «only one should be named», does so without this implying that one of the two forms is more real than the other. The Light must not be identified with the first way. Men name two forms, light and night, and this is the mistake, since one should be named, "what is".[125] Guthrie, who makes a critical compilation of all the positions on the matter, does not find Cornford and Diels' objection to Zeller's translation convincing, since Parmenides' expression is irregular. Cornford's translation would also be better represented by the textual presence of a οὐδὲ μίαν (udé mían, «none») and that of Simplicius and Raven by a μίαν μόνην (mían mónēn, «only one» ).[126] Guthrie argues that Parmenides thinks that it is illogical to accept, on the one hand, that the world contains a plurality of things, and on the other, that this plurality can arise from a single principle.[127] The passage from the way of truth to the deceptive words of mortal opinions is a real problem for specialists. Even when the goddess tells the "man who knows" that she reveals this order to him as plausible, so that no mortal can outdo him (vv. 60–61), this reason has been interpreted in various ways. In antiquity, Aristotle conceived the first part of the poem as the consideration of the One κατὰ τὸν λόγον (katá tón lógon, «regarding the concept»[128] or "as to definition" or "as to reason"[129]), and the second as the consideration of the world according to the senses (Met 986b31 = A 24). Theophrastus followed him at this point,[130] and Simplicius adds that, although the goddess calls the speech of the second part "conjectural" and "misleading", she does not consider it completely false (Physics 39, 10–12 = A 34). Jaeger, following Reinhardt,[131] he thought that Parmenides was presented with the need to explain the origin of the deceptive appearance. And he had no other means than to narrate the origin of the world constituted by appearances, that is, to compose a cosmogony.[132] Owen argues that the content of the second part is merely a dialectical device, and does not imply an ontological claim.[133]

B9: Day and Night

Fragment 9 mentions again what was described in the final part of Fragment 8 as what mortals have conceived as the dual foundation of the world of appearance: the opposing principles "light" and "night", and says that everything is full of these opposites, and that nothing belongs exclusively to one of the two. In Fragment 9, Parmenides goes a step further, and states that the entire sensible realm can be reduced to manifestations of this pair of opposites, night and light (Gresi: φάος, v.1), and that both penetrate the whole of reality equally.[56] These forms can be considered to head a list of opposites, which serve as qualities to sensible things.[134]

The idea of grouping under the fundamental opposite pair all the attributes of it has its parallel in the table of opposites of Pythagoras.[135] Of course, in the Parmenidean table, oppositions that are not sensible must be excluded.[136] For Simplicius,[137] it was clear that assigning fire the attribute of agent, which Alexander of Aphrodisias had done,[138] was a mistake. The reliability of all such evidence dependent on Aristotle is now highly doubted,[139] even when they reflect previous cosmogonic beliefs and it is not too risky to consider fire as active and earth as passive.[134]

The fact that the goddess indicates (v.3-4) that everything is full of both night and light "equally" (ἴσων ἀμφοτέρων, ísōn amphotérōn) is ambiguous; it could either mean "of equal rank," which would agree with Aristotle's interpretation, according to which one form "is" and the other "is not,"[140][56][141][142] or it could refer to an equality in quantity or extension, which would parallel a Pythagorean expression[143] where in the cosmos, light and darkness are posited to equally cover (ἰσόμοιρα) the earth.[134]

B10-15: Cosmology

Although the second half of the poem is less well preserved, a rough outline of Parmenides' cosmology can still be tentatively reconstructed on the basis of the surviving fragments along with testimony of his philosophical theories from ancient doxographers, especially Aetius and Plutarch. Plutarch says in adv. Colotem 1114b (A10) that, from the original opposites, Parmenides elaborates an order in which the Earth, the heaven, the Sun, the Moon, the origin of man, and that he "did not fail to discuss any of the important questions." Simplicius,[144] says that Parmenides also dealt with the parts of animals. Plato places him alongside Hesiod as the creator of a theogony,[145] and Cicero[146] reports that the poem contained certain Hesiodic abstract divinities,[147] such as Love, War and Discord.[148]

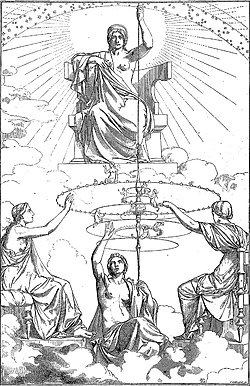

Fragments 10 and 11, which are introductory to cosmology, confirm what is expressed by the testimonies, at least with regard to the Sun, the Moon, and the sky, although it also includes the aether, the stars, the constellations (n.b.: the word σήματα used by Parmenides can mean both "constellations" and "signs")[56] and the Milky Way, and mythical elements such as Mount Olympus. The Parmenidean goddess presents a cosmic order in fr. B12[149] and the summary of Aetius[150] that is extremely difficult to reconstruct, due to the scarcity and obscurity of the fragments.[56][151][56] The beginning of fragment 12 and the testimony of Aetius [152] introduce into cosmology certain "rings"[153]) The existence of concentric rings of a diverse nature is postulated as the structure of the cosmos: some rings were of pure fire and others of a mixture of fire and darkness, the rings closer to the center participated more in fire, while those further from the center were more filled with night. There are also rarified and dense ones. Surrounding everything is a solid wall. The doctrine of the rings seems to be the influence of Anaximander[154] and of Hesiod,[155] who speaks of the "crowned" sky and the stars. At the center of the system, an unnamed daimon[156] coordinates all the cosmological elements, both sensible opposites and Necessity, and presides over the mixture and attraction of the sexes, and the "abhorrent" birth.[157] Plutarch[158] calls her Aphrodite, before citing fragment 13 of her, which marks her as the mother of Eros, while Aetius identifies her with Ananke and also Dike, Δίκη, present in the proem, here presiding over movement and birth.

Fragment 10 gives a predominant role to Ananke(Ἀνάγκη, Anánkē), the personification of Necessity, which obliges Heaven to keep the stars within its limits (πεῖρατα).[56] The role of Necessity in this system has been compared to the one Plato gives it in the Myth of Er.[159] There Plato places it in the center of certain concentrically arranged turrets, each one representing the celestial spheres that support the fixed stars, the nearby heavenly bodies, the planets, the Moon and the Sun.[160][161][56] Both this cosmology and the Myth of Er also have similarities with Pythagorean cosmology, where the center of the universe was generally identified with Hestia (in non-geocentric Pythagorean systems such as Philolaus) and with Mother Earth (in geocentric Pythagorean systems).[162] Diogenes Laertius claims that to Parmenides was the first to state idea that the Earth has a spherical shape and that it is located in the center,[163] but he also cites testimonies that affirm that it was Pythagoras and not Parmenides who held these ideas[164] and also that it was Anaximander.[165] Beyond the evident doubts that these contradictory affirmations generate, Guthrie believes that in this Parmenides followed Pythagoras in the general lines of the description of the physical world.[166]

Various reconstructions of the concentric annular strata and their identification with the substantial elements of the cosmos have been attempted:

- The solid wall that surrounds everything is sometimes identified with the ether,[167][168] or as distinct from all other elements.[169]

- The ethereal ring of pure fire is where the morning star is located.[169]

- Rings of mixed nature. The upper ring of these is the sky proper where the Sun is, and a little lower down, the stars, the Milky Way and, closer to the dense rings, the Moon.[168][169]

- The dense rings, whose substance is night, are usually identified with the Earth.[168][167][169]

Fragments 14 and 15 refer to the Moon: alien light (ἀλλότριον φώς) shining around the Earth» and always looking at the Sun, which has been interpreted as the observation that the Moon reflects the rays of the Sun.[56] Aetius attributes this view Parmenides,[170] but claims that Thales had already said it, and later Parmenides and Pythagoras added to this,[171] On the other hand, Plato attributes the idea to Anaxagoras, and elsewhere Aetius says that Parmenides thought that the Moon was made of fire (A 43) —implying that he thought he had his own light.[172] In the Homeric poems,[173] "alien light" simply means "foreigner", without reference to light.[172]

In fragment 15a there is only one word: ὑδατόριζον:(hydatórizon, “rooted in water”) an adjective referring, according to its transmitter (Basil of Caesarea), to Earth. This idea has been compared to the Homeric tradition that conceived of Ocean as the origin of all things,[174][175] as a more general allusion to the Homeric world, which located various rivers in Hades,[176][166] to the roots of the Earth mentioned by Hesiod[177] and Xenophanes,[178] or to Thales of Miletus's view that the Earth floated on water.[179]

B16: Sense perception

Parmenides also provided a theory of knowledge through sense perception, a description of which is preserved by Theophrastus. Theophrastus, in recording Parmenides' opinion on sensation,[s] indicates that Parmenides holds that sense perception proceeds by resemblance between what feels and the thing felt. He reports Parmenides as saying that everything is composed of two elements, hot and cold, and their intelligence depends on this mixture, present in the limbs of humans. In fact, the nature of each limb or organ, what is preponderant in them, is what is perceived. That is why corpses, which have been abandoned by fire, light and heat, can only perceive the opposite, cold and silence. Everything that exists, he concludes, contains some knowledge. Just as Empedocles later said that "we see earth with earth, water with water" ,[t] he held, in accordance with his doctrine of sensible opposites, that mortal perception depends on the admixture of these opposites in the different parts of the body (μέλεα). But, following his teacher's interpretation of the Parmenidean opposites, he says that the thought that arises from the hot is purer. Fränkel therefore thought that this theory of knowledge was valid not only for sensory perception, but also for the thought of "what is".[180] Vlastos maintains that the identity of the subject and the object of thought is valid both for the knowledge of what is (B3) and for sensible knowledge, although he accepts that «what is" is "everything identical" (B8, v. 22), while the structure of the body is a mixture of different elements,[181] and that the preponderance of light does not physically justify the knowledge of "what is". The way to conceive a pure knowledge is not by imagining a situation in which the body has more light, but that it is made of pure light, and this is what Parmenides does in the journey recounted in the proem.[182] Other commentators disagree with transposing this "physical" explanation to the plane of the path of truth. Guthrie[183] and Schofield[56] emphasize the exclusive belonging of this theory to the field of the sensible, of mortal opinion.

B17-18: Embryology

Parmenides cosmology also included medical theories: two testimonies[184] indicate that Parmenides was interested in embryology, and two fragments, preserved by Galen (B17), and Caelius Aurelianus (B18) are from medical contexts.

Parmenides' theory of embryology claims that each of the sexes is conceived on a different side in the mother's womb:[u] the sex of the embryo depends, on the one hand, on the side from which it is conceived in the womb, and on the other, on the side from which the father's seed comes. But the character and traits of the begotten being depend on the mixture of masculine and feminine potencies (B18). So that:

- If the semen comes from the right side and lodges in the right side of the womb, the embryo will be a well-built and masculine man.

- If the semen comes from the left side and lodges in the left side of the womb, the result is a female with feminine features.

- When the semen comes from the left, and lodges to the right of the uterus, it gives rise to a man, but with feminine traits such as outstanding beauty, whiteness, small stature, etc.

- If the semen originates on the right and descends to the left of the uterus, this time it forms a woman, but with markedly masculine traits: virility, excessive height, etc.[185]

This medical theory exhibits similarities to the medical doctrine of Alcmaeon of Croton,[186] which conceived an "equal distribution" (ἰσονομία) of forces between man and woman in determining the child's sex,[56] and contrasts with the later theory of Anaxagoras, to whom Aristotle[187] attributes the theory that only male seed determines sex.[185]

Parmenides' association of boys with "the right" and girls with "the left" in Fragment B17, combined with the testimony of Aristotle (A52) and Aetius (A53) attribute to Parmenides the view that the masculine is associated with the cold and the dense,[188] and the feminine with the hot and diffuse,[189] upsets the general Greek conception, which associates right with light and warm, and left with dark and cold,[136] but resembles a Pythagorean Table of opposites, leading some scholars[v] to postulate that Parmenides probably carried out an outline of Pythagorean cosmology. However, on the other hand, many of the other opposites in the Pythagorean table are never mentioned by Parmenides, there are elements completely unrelated to Pythagoreanism, such as the "rings" in fragment 12, and no ancient commentators claimed to find any traces of Pythagorean doctrine in his poem, instead the Way of Opinion is unanimously considered to be Parmenides' own invention.[190] Another possibility is that, unlike in cosmology, Parmenides did not see masculine and feminine as pure opposites in embryology, where observation and empirical guidance allowed for a greater variety of opinions on the role of males.[136]

B19: Conclusion

Fragment B19,[191] located at the conclusion of the Way of Opinion, reaffirms the concepts expressed before[192] that the cosmos belongs to the Way of Opinion (v. 1), that the things with in the cosmos come to be and pass away (v. 1 and 2), and that these things are predicated on names assigned by mortals (v. 3).[193]

Dating, style and transmission

In the introduction to the poem,[w] the goddess speaks to the recipient of the message, presumably Parmenides himself, calling him κοῦρε (koûre, "young man"). It has been suggested that because this word refers to a man no older than thirty years and, taking into account Parmenides' date of birth, we can place the creation of the poem between 490 BC and the 475 BC[15][56] But it has been objected that the word must be understood in its religious context: it indicates the relation of superiority of the goddess with respect to the man who receives the revelation from her.[194] Guthrie supports this idea, supporting it with a quote (Aristophanes, The Birds 977) where the word precisely indicates not the age of a man (which otherwise he is not young), but rather his situation with respect to the interpreter of oracles by whom he is being questioned. His conclusion is that it is impossible to say at what age Parmenides wrote the poem.[195]

Much has been said about the poetic form of his writing. Plutarch considered it to be just a way of avoiding prose,[x] and criticized its versification.[y] Proclus said that despite using metaphors and tropes, forced by the poetic form, his writing is more like prose than poetry.[z] Simplicius, to whom we owe the preservation of most of the text that has come down to us, holds a similar opinion: one should not be surprised at the appearance of mythical motifs in his writing, due to the poetic form he uses.[aa] For Werner Jaeger, Parmenides' choice of the didactic epic poem form is a highly significant innovation. It involves, on the one hand, the rejection of the prose form introduced by Anaximander. On the other hand, it means a link with the form of the Theogony of Hesiod. But the link affects not only the form, but also certain elements of the content: in the second part of Parmenides' poem (fragments B 12 and 13) Hesiod's cosmogonic Eros appears (Theogony 120) along with a large number of allegorical deities such as War, Discord, Desire,[ab] whose origin in the Theogony cannot be doubted. However, putting these cosmogonic elements in the second part, dedicated to the world of appearance, also involves the rejection of this way of understanding the world, a way alien to the Truth for Parmenides. Hesiod had presented his theogonic poem as a revelation from divine beings. He had made the invocation of the muses —already an epic convention— the story of a personal experience of initiation into a unique mission, that of revealing the origin of the gods. Parmenides in his poem presents his thought on the One and Immobile Entity as a divine revelation, as if to defeat Hesiod at his own game.[196]

Parmenides's poem, as a complete work, is considered irretrievably lost. From its composition, it was copied many times, but the last reference to the complete work is made by Simplicius, in the 6th century: he writes that it had already become rare by then ('Physics' ', 144).[197] What comes to us from the poem are fragmentary quotes, present in the works of various authors. In this Parmenides does not differ from the majority of the Pre-Socratic philosophers. The first one who cites it is Plato, then Aristotle, Plutarch, Sextus Empiricus and Simplicius, among others. Sometimes the same group of verses is cited by several of these authors, and although the text of the citations often coincide, other times they present differences. This gives rise to arguments and speculations about which quote is the most faithful to the original. There are also cases in which the citation is unique.[198] The reconstruction of the text, starting from the reunion of all existing citations, began in the Renaissance and culminated in the work of Hermann Diels, Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, in 1903, which established the texts of most of the philosophers prior to Plato.[199] This work contains a total of 19 presumably original "fragments" of Parmenides, of which 18 are in Greek and one consists of a rhythmic translation in Latin. 160 verses of the poem have been preserved. According to Diels' estimates, these lines represent about nine-tenths of the first part (the "way of truth"), plus one-tenth of the second (the "way of opinion").[200] Diels' work was republished and modified by Walther Kranz in 1934. The edition had such an influence on studies that today Parmenides (as well as the other pre-Socratics) is cited according to the order of the authors and fragments of it. Parmenides occupies chapter 28 there, so he is usually cited with the abbreviation DK 28, then adding the type of fragment (A = ancient commentaries on life and doctrine; B = the fragments of the original poem) and finally the number. snippet (for example, "DK 28 B 1"). Even though this edition is considered canonical by philologists, numerous reissues have appeared that have proposed a new order of the fragments, and some specialists, such as Allan Hartley Coxon, have made collations on the manuscripts in which some of the quotations are preserved, and have questioned the reliability of the reading and establishment of Diels's text.[201]

Legacy and study

As the first of the Eleatics, Parmenides is generally credited with being the philosopher who first defined ontology as a separate discipline distinct from theology.[4] Parmenides was the first Western philosopher to consider the nature of existence itself,[42] While previous philosophers like the Milesians developed theories of how things physically originated, Parmenides considered ontology, or how things are, solely as an idea without reference to a physical basis.[43] He likely rejected the theories of the Milesian school, which described the world as being derived from specific elements, as Parmenides rejected that Being was derived from anything.[202]

Though his ideas preceded and influenced metaphysics, modern philosophers do not consider Parmenides to have studied metaphysics himself, as Being is not a distinct entity from the physical world. Some exceptions exist, such as Pierre Aubenque, who described Parmenides' work as "the birth certificate of Western metaphysics".[203] Parmenides has been seen as the first Western philosopher to invoke what are now considered the basic principles of logic. His concepts of Being and Nonbeing are defined by the law of noncontradiction; since Being is, it cannot not be, and since Nonbeing is not, it cannot be. The law of excluded middle prevents the existence of something that neither is nor is not.[204] The principle of sufficient reason indicates that Being must be if it can be thought about, as a thought is something rather than nothing. Parmenides' conclusion is defined by the law of identity, as Being is to be and Nonbeing is to not be. By combining these logical processes, Parmenides proves a tautology using a syllogism.[205]

Parmenides understood the Moon's illumination to be the reflection of sunlight off of its spherical surface. He is sometimes described as the first philosopher to describe the Earth as spherical and to identify the morning star and the evening star were both manifestations of a single object, Venus.[49]

Ancient philosophy

Pre-Socratic philosophy

In modern interpretations, Parmenides is often seen as presenting a theory of unchanging "being" that spurred debate about the nature of change among subsequent natural philosophers in Presocratic philosophy.[206] However, there is no ancient testimony that supports this notion, and most interpreters of Parmenides in Antiquity appear to have read Parmenides as considering metaphysics and physics as two different aspects of the same reality.[206] Parmenides was a contemporary of Heraclitus. The two broached many of the same ideas, such as a world made of two competing opposites, reliability of the senses, and the nature of plurality—it is unclear if either influenced the other.[207]

Parmenides' philosophy formed the basis of the Eleatic school, which was continued by Melissus of Samos and Zeno of Elea. Melissus built on Parmenides' ideas, proposing a continuous eternal Being instead of a constant existence of the present. Zeno created reductio ad absurdum arguments to defend Parmenides' ideas against their critics.[208]

In his work On Non-Being, Gorgias includes both Parmenides and Melissus as philosophers who held that reality is one.[206] The pluralist theories of Empedocles and Anaxagoras and the atomists Leucippus and Democritus have also been seen as a potential response to Parmenides's arguments and conclusions.[209]

Plato

Along with Socrates and the Pythagoreans, Parmenides was one of the greatest influences on Plato.[206]

In different places, Aristotle attributes the same epistemological position to Parmenides[210] that he does to Plato,[211] that true knowledge must be grounded in an entity that is not subject to change.[206] This position is also endorsed by Plato himself at the end of the 5th book of the Republic.[206] For Plato, these are the forms from his own Theory of Forms.[206] In his own Parmenides, Plato presents a fictional dialogue between Socrates and Parmenides where Parmenides himself also endorses this doctrine, that knowledge must be built on something unchanging.[206]