Ehsan Danish

The Saint Thomas Christian denominations are Christian denominations from Kerala, India, which traditionally trace their ultimate origins to the evangelistic activity of Thomas the Apostle in the 1st century.[1][2][3][4] They are also known as "Nasranis" as well. The Syriac term "Nasrani" is still used by St. Thomas Christians in Kerala. It is part of the Eastern Christianity institution.

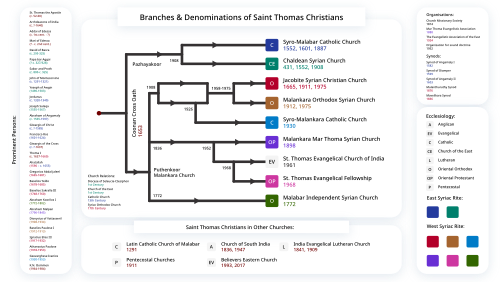

Historically, this community formed a part of the Church of the East, served by metropolitan bishops and a local archdeacon.[5][6][7] By the 15th century, the Church of the East had declined drastically,[8][9] and the 16th century witnessed the Portuguese colonial overtures to bring St Thomas Christians into the Latin Catholic Church, administered by their Padroado, leading to the first of several rifts (schisms) in the community.[10][11][12] The attempts of the Portuguese culminated in the Synod of Diamper in 1599 and was resisted by local Christians through the Coonan Cross Oath protest in 1653. This led to the permanent schism among the Thomas' Christians of India, leading to the formation of Puthankoor (New allegiance, pronounced Pùttankūṟ) and Pazhayakoor (Old allegiance, pronounced Paḻayakūṟ) factions.[13] The Pazhayakoor comprise the present day Syro-Malabar Church and Chaldean Syrian Church which continue to employ the original East Syriac Rite liturgy.[5][14][15][16] The Puthankoor group, who resisted the Portuguese, organized themselves as the independent Malankara Church,[17] entered into a new communion with the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch, and they inherited the West Syriac Rite from the Syriac Orthodox Church, which employs the Liturgy of Saint James, an ancient rite of the Church of Antioch, replacing the old East Syriac Rite liturgy.[18][5][19]

List of churches

- Assyrian Church of the East

- Eastern Catholic

- Oriental Orthodox

- Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (Syro-Antiochene Rite, claim autocephality )

- Jacobite Syrian Christian Church (Syro-Antiochene Rite, autonomous, under the Syriac Orthodox Church)

- Malabar Independent Syrian Church (Syro-Antiochene Rite), independent, officially not part of Oriental Orthodox Communion)

- Oriental Protestant

- Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church (Syro-Antiochene Rite – Oriental Protestant, independent)

- St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India (Syro-Antiochene Rite – Oriental Evangelical, independent)

- Apart from the above churches which claim Thomas as their founder, Nasranis can also be found in Protestant churches. They are,

- Saint Thomas Anglicans of the Church of South India (United Protestant denomination that holds membership in the Anglican Communion, World Methodist Council and World Communion of Reformed Churches)

- Pentecostal Saint Thomas Christians (Charismatic),[20][21][22][23] groups tracing their history back to the Malankara Church include the Kerala Brethren, Church of God (Kerala State),[24] and Indian Pentecostal Church of God.[25]

Overview

The Saint Thomas Christians of Kerala belong to a unique Eastern Christian tradition blended in the changing socio-cultural environment of their homeland in Southern Indian subcontinent.[26] Thus, the community is often defined as Hindu or Indian in culture, Christian in religion, and Syriac-Oriental in terms of liturgy and worship.[26]

Their traditions date to first-century Christian thought, and the seven "and a half" churches established by Thomas the Apostle during his mission in Malabar.[27][28][29] These are located at Kodungalloor (Muziris), Paravur, Palayoor, Kokkamangalam, Niranam, Nilackal, Kollam, and the Thiruvithamcode Arappally in Kanyakumari district.

Saint Thomas Christian families who claim their descent from ancestors who were baptized by Apostle Thomas are found throughout Kerala.[30][26] St. Thomas Christians were classified into the social status system according to their professions with special privileges for trade granted by the benevolent kings who ruled the area. After the 8th century when Hindu kingdoms came to sway, Christians were expected to strictly abide by stringent rules pertaining to caste and religion. This became a matter of survival. This is why St. Thomas Christians had such a strong sense of caste and tradition, being the oldest order of Christianity in India. The Archdeacon was the head of the Church, and Palliyogams (Parish Councils) were in charge of temporal affairs. They had a liturgy-centered life with days of fasting and abstinence. Their devotion to the Mar Thoma tradition was absolute. Their churches were modelled after Jewish synagogues.[26] "The church is neat and they keep it sweetly. There are mats but no seats. Instead of images, they have some useful writing from the holy book."[31][32]

The Nasranis constitute two distinct ethnic groups, namely the Vatakkumbhagar and Tekkumbhagar, which share a common cultural history.[33] As a community with common cultural heritage and cultural tradition, they refer to themselves as Nasranis.[33] However, as a religious group, they refer to themselves as Marthoma Khristianikal (or in English as 'Saint Thomas Christians'), based on their religious tradition of Syriac Christianity.[33][34][35]

However, from a religious angle, the Saint Thomas Christians of today belong to various denominations as a result of a series of developments including Portuguese persecution[36] (a landmark split leading to a public Oath known as Coonen Cross Oath), reformative activities during the time of the British (6,000—12,000 Jacobites joined the C.M.S. in 1836, after the Synod of Mavelikara; who are now within the Church of South India), doctrines and missionary zeal influence (Malankara Church and Orthodox-Jacobite dispute (division of Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church and Malankara Jacobite Syriac Orthodox Church (1912)).

The Eastern Catholic faction is in full communion with the Holy See in Rome. This includes the aforementioned Syro-Malabar Church as well as the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church, the latter arising from an Oriental Orthodox faction that entered into communion with Rome in 1930 under Bishop Geevarghese Ivanios (d. 1953). As such the Malankara Catholic Church employs the West Syriac liturgy of the Syriac Orthodox Church,[37] while the Syro-Malabar Church employs the East Syriac liturgy of the historic Church of the East.[5]

The Oriental Orthodox faction includes the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church and the Jacobite Syrian Christian Church, resulting from a split within the Malankara Church in 1912 over whether the church should be autocephalous or rather under the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch.[38] As such, the Malankara Orthodox Church is an autocephalous Oriental Orthodox Church independent of the Patriarch of Antioch,[38] whereas the Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church is an integral part of the Syriac Orthodox Church and is headed by the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch.[18]

The Iraq-based Assyrian Church of the East's archdiocese includes the Chaldean Syrian Church based in Thrissur.[39] They were a minority faction within the Syro-Malabar Church, which split off and joined with the Church of the East Bishop during the 1870s. The Assyrian Church is one of the descendant churches of the Church of the East.[40] Thus it forms the continuation of the traditional church of Saint Thomas Christians in India.[41]

Oriental Protestant denominations include the Mar Thoma Syrian Church and the St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India.[42] The Marthoma Syrian Church were a part of the Malankara Church that went through a reformation movement under Abraham Malpan due to influence of British Anglican missionaries in the 1800s. The Mar Thoma Church employs a reformed variant of the liturgical West Syriac Rite.[43][44] The St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India is an evangelical faction that split off from the Marthoma Church in 1961.[45]

CSI Syrian Christians are a minority faction of Malankara Syrian Christians, who joined the Anglican Church in 1836, and eventually became part of the Church of South India in 1947, after Indian independence. The C.S.I. is in full communion with the Mar Thoma Syrian Church.[46][47][48][49] By the 20th century, various Syrian Christians joined Pentecostal and other evangelical denominations like the Kerala Brethren, Indian Pentecostal Church of God, Assemblies of God, among others. They are known as Pentecostal Saint Thomas Christians.[50][51]

History

16th century

Christians in India were part of the Church of the East up until the late 16th century.[52]

Following the schism of 1552 in the Church of the East and the formation of the Chaldean Catholic Church, both the traditional and the Chaldean Catholic factions sent bishops to India.[53] The first of the Chaldean Catholic bishops in India was Yawsep Sulaqa, the brother of the first Chaldean Patriarch Yohannan Sulaqa.[54] Another bishop, Abraham, arrived in India as a traditionalist bishop but later joined the Catholic faction.[5]

Synod of Diamper and Coonan Cross Oath

Abraham was to become the last Chaldean bishop to govern the undivided Saint Thomas Christian community. Following his death in 1597, the Portuguese missionaries started a vigorous and comprehensive process of Latinisation in liturgy among the local Christians and started preventing other East Syriac bishops from reaching Malabar.[54] These efforts culminated in the so-called Synod of Diamper (1599), the local clergy was forced to reject the Chaldean Catholic patriarch of Babylon, who in fact was in full communion with Rome at that time, as a Nestorian heretic and schismatic.[55][54] The Portuguese occupied the diocesan administration of the Saint Thomas Christians and deprived the archdeacon of his traditional rights.[56] This provoked a strong reaction from the local Christians, led by their archdeacon Thoma Parambil, in the form of the Coonan Cross Oath.[57][5] Although the exact wording of the oath is disputed, its effect was the severing of the relationship between the local Christians and the Portuguese and the proclamation of the archdeacon as their new metropolitan with the title 'Mar Thoma'.[58][59]

Reunion with Rome and resulting schism

In 1656, Pope sent an Italian 'Disclaced' Carmelite priest named Giuseppe Maria Sebastiani to reunite the Saint Thomas Christians who had separated themselves from the jurisdiction of the existing Catholic bishop through the Coonan Cross Oath.[60] In 1663, he consecrated Chandy Parambil as the local bishop, after the Dutch, having defeated the Portuguese, banned other Europeans from operating in Malabar.[61][62]

Meanwhile, Thoma I wrote letters seeking help from other Eastern churches.[63] In response, a Syriac Orthodox bishop named Gregorios Abdal Jalīl arrived in Malabar in 1665 and regularised Thoma's episcopacy.[5] Succeeding Thoma, senior priests in his Pakalōmaṯṯam dynastic line took over as the leaders of the faction that had remained aligned to him. They continued to maintain strong relations with the Syriac Orthodox Church. Over time, they adopted the West Syriac Rite instead of the old East Syriac Rite. Thus the split in the Saint Thomas Christian community solidified and those who descend from Thoma's faction came to be called Puthankoottukar (Puttankūṯṯukāṟ or 'those of the new allegiance') and those of Chandy came to be called Pazhayakoottukar (Paḻayakūṯṯukāṟ or 'those of the old allegiance').[64][65]

Pazhayakoottukar

Under the Latin hierarchy

After the death of Chandy, Carmelite missionaries regained the leadership of the Pazhayakoottukar and were reluctant to consecrate native bishops any further.

Early attempts at reunion with the Chaldean Patriarchate

Throughout the seventeenth century, there were no notable interactions between the East Syriac communities in Malabar and that in Assyria. Intermittent attempts to restore the lost hierarchical links initiated in the early 18th century as two East Syriac bishops, namely Shemʿon of ʿAda and Gabriel of Azerbaijan, came to India at the request of the Indian Christians. Shemʿon arrived in India in 1701 and was imprisoned by the Latin missionaries on his arrival. Hoping for support and yielding to their insistence, he consecrated Angelo Fransisco Vigliotti in Alangad, who was denied episcopal consecration by the Portuguese bishops in India, as the first Apostolic vicar of Verapoly. However Vigliotti and the missionaries were quick to transport Shemʿon back to their monastery in Mylapore where he was later found dead in a well. Gabriel arrived in Malabar after 1705 following Shemʿon's arrival and was cautious enough to protect himself from being captured by Latin missionaries. He established himself as metropolitan and was able to consolidate significant support among both Pazhayakoottukar and Puthankoottukar. Under the protection of the Dutch, he was able to mount a strong resistance against the Carmelite missionaries and also Thoma IV, the Syriac Orthodox-leaning Puthankoor leader, until his death. However he failed to establish a continuous line of succession in India and his followers had to return to their previous allegiances after his death.

Late 18th century

In the latter half of the 18th century the representatives of Pazhayakoor (Paḻayakūṟ or 'old allegiance') churches met in Angamaly and assigned Yawsep Kariyāṯṯil and Thoma Pārēmmākkal to travel to Rome to meet the Pope to receive Dionysios I, the leader of the Puthankoottukar, into the Catholic Church.[66] Their request was not accepted in Rome, due to the insistence of the Carmelites. Meanwhile, the Portuguese appointed Kariyaṯṯil as archbishop under the padroado in order regain its lost power among the Saint Thomas Christians.[67] However he could not assume power as he died in Goa, in dubious circumstances at the age of 49, way before arriving in Malabar.[66][61][67] The Portuguese appointed his successors and thus the Pazhayakoor faction was divided under two systems, the Archdiocese of Cranganore of the Portuguese and the Apostolic vicariate of Verapoly of the Carmelites.[61]

The late 18th and the early 19th century also witnessed a successful but short-lived attempt of the Pazhayakoottukar led by Paulose Pandari to re-establish the historical ties with the patriarchate. In 1787, the Pazhayakoottukar drew up the Angamāly Padiyōla expressing their desire to re-establish relations with the Chaldean Patriarchate.[67] In response, the Chaldean Patriarch Yohannan VIII Hormizd consecrated Priest Paulose Pandāri from Puthenchira as their metropolitan.[68] Pandāri was able to achieve a brief reunion with Dionysios I but was recalled by the patriarch at the insistence of Rome.[69]

Later attempts at reunion with Chaldean Patriarchate

It was only in the 19th century that correspondence with the East Syriac patriarchate was revived. Protests against the Latin Carmelite missionaries were strong among the Pazhayakoottukar. Monk Anthony Kudakkachira stepped forward to take the lead in the local resistance. Consequently in 1852, a group of Syrians, led by Monk Anthony Kudakkachira, went to Baghdad to meet Chaldean Patriarch Yawsep VI and to request bishops to be appointed to the Chaldeans in Malabar. He was accompanied by Anthony Thondanatt, who took up the mission after his death. Patriarch Yawsep VI, without waiting for permission from Rome, sent Metropolitan Thoma Rokkos as his representative to Malabar in 1861. Most Pazhayakoottukar declared their allegiance to him. This compelled Bishop Bernardine Beccinelli, the Vicar apostolic of Verapoly, to appoint a Pazhayakoor priest, namely, Kuriakose Elias Chavara, as his Vicar general for the Syrian Chaldeans under his vicariate. Pope Pius IX issued an ultimatum to Yawsep VI to recall Rokkos from India or face excommunication and Rokkos finally withdrew from Malabar in 1862. Anthony Thondanatt followed Metropolitan Rokkos to Baghdad in 1862 in an attempt to persuade the patriarch to consecrate a native priest of Malabar to the episcopacy but the patriarch, who was facing increasing threats from Rome, declined to do so. Therefore Thondanatt approached the Assyrian Patriarch Shimun XVIII who consecrated him as metropolitan with the title Abdisho. But on returning to Malabar, he found himself unacceptable to the natives as he was consecrated by the Assyrian Patriarch rather than the Chaldean.[70]

In 1874, Patriarch Yawsep VI sent Metropolitan Elias Mellus to Malabar in response to the renewed pleas for a bishop. He was accompanied by Corebishop Michael Agustinos and soon followed by Bishop Philip Yaqov Abraham. Most of the Syrian churches under the padroado and some of the churches under Verapoly submitted to Mellus. Following this, Pope Pius IX excommunicated Patriarch Yawsep VI and Metropolitan Elias Mellus, for the patriarch's unauthorised intervention in Malabar. To relieve himself from the pope's excommunication, the patriarch was left with no other option than to recall the metropolitan from Malabar, which he reluctantly did in 1882.[71]

Formation of the Chaldean Syrian Church

Union with the Assyrian Patriarchate

Meanwhile, Metropolitan Mellus had entrusted his followers (or 'Mellusians') to his assistant Corebishop Michael Agustinos. They retained the name 'Chaldean Syrian Church' which was used to denote the Pazhayakoor church. Abdisho Thondanatt was finally brought to Thrissur and recognised as their bishop. Thondanatt died in 1900, leaving the followers of Mellus without a bishop. Corebishop Agustinos had been trying to bring a bishop from the Chaldean patriarch, but he was not willing to do so as he had strict orders from Rome not to take any such steps. Hence they approached the Assyrian Patriarch, and he appointed Abimalech Timotheus as Metropolitan of India. Abimalech, influenced by Anglican Protestant thought, started a process of iconoclasm among the Mellusians. He pulled down the raredos of the churches and destroyed the statues and images. He also started a programme of replacing the old Malabar usage of the East Syriac Rite liturgy with the Rite of the Assyrian patriarchate. This created a new rift among the Mellusians. Those, who opposed the radical stance of Metropolitan Abimalech organised themselves under Corebishop Augustinos and were known as Independents, while those who stood with Abimalech were called 'Surayis'. The two factions engaged in legal suits, which the Independents finally lost, and the independents ultimately joined the Syro-Malabar Church.[72]

Schism and reunion

Abimalech was succeeded as metropolitan by Thoma Darmo in 1952. In the 1960s, Darmo and Patriarch Shemʿon XXI Eshai engaged in a bitter rivalry and in 1968, Darmo was elected as a rival patriarch, thus creating the Ancient Church of the East. He consecrated two Indian bishops, including Aprem Mooken who became his successor as Metropolitan in Trichur. In 1971 Patriarch Shemʿon XXII consecrated a rival Metropolitan for Malabar, paving way to full blown schism in the Chaldean Syrian church. In 1995, the two factions united under Metropolitan Aprem and Assyrian Patriarch Dinkha IV.[72]

Establishment of the Syro-Malabar Church

The rising tensions between the Pazhayakoottukar and the Carmelite missionaries forced Rome to change its policy as it realised that granting true autonomy and self-government to the Pazhayakoottukar was the only feasible solution.[73][74] In 1887, the Syrian Catholics were formally separated from the Vicariate of Verapoly, which was left for the Latin Catholics, and two new apostolic vicariates were established for the Syrians based in Kottayam and Thrissur. In 1896, they were reorganized into three vicariates namely, Trichur, Ernakulam, and Changanacherry, under the guidance of native bishops.[61] This paved the way for the foundation of the modern Syro-Malabar Church.[74] In 1911, a new vicariate was founded for the Pazhayakoor Thekkumbhagar (Tekkumbāgaṟ or Southists or Knanaya) based in Kottayam, following a similar event among the Puthankoor Thekkumbhagar in 1910.[73][61] In 1923, Rome established a complete Syro-Malabar Catholic hierarchy with the Archbishop of Ernakulam as the head. In 1992, the church was declared a major archiepiscopal church.[61]

Puthankoottukar

The Puthankoor faction of the Saint Thomas Christian community which remained unwilling to restore ties with the Catholic Church and the Pope and instead chose to align with the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch. They organised themselves as the 'Malankara Church' and developed a relationship with the Syriac Orthodox Church starting in 1665, when Thoma I was recognised as their legitimate bishop by the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch. Thoma I was succeeded by dynastic priests from his Pakalomattam family. Their relationship with the Syriac Orthodox Church gradually strengthened over the years. Thus they changed their liturgical rite from East Syriac to West Syriac, a process which was complete by the 19th century. This also led to emergence of resentment towards the ever-growing authority of the Patriarch of Antioch in the Puthankoor Malankara Church. Thus this church suffered further divisions in the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries, resulting in the formation of multiple Malankara churches.[75]

18th century

Although Thoma I and his dynastic successors recognized the spiritual authority of the Patriarch of Antioch and the Syriac Orthodox theology. However they were reluctant to compromise their local church governance rights in any way.

In the 18th century, a delegation of three Syriac Orthodox prelates led by Maphrian Baselios Shukr-Allah arrived in Malabar during the reign of Thoma VI. Very soon, a power struggle broke out between him and the Syriac Orthodox bishops. Thoma VI was initially hesitant to submit to the delegation and was unwilling to receive Holy Orders afresh from them as they had declared his orders to be invalid.[76] Thoma responded by trying to reunite with the Catholic Church under the Pope by collaborating with kindred spirits in the Pazhayakoor faction, such as Yousep Kariyattil and Paremmakkal Thoma. Frustrated of his defiance, Gregorius Hanna, one of the Syrian Orthodox bishops, consecrated Kurillos as his rival in an attempt to secure their foothold in the Malankara Church. However Thoma's reunion attempt with the Catholic Church failed due to opposition from the Carmelite missionaries, and by then Thoma finally yielded to the demands and received ordination and consecration anew from the Syrian Orthodox bishops and changed to the episcopal name Dionysios I in return for their support against Bishop Kurillos.[77] The dispute between Kurillos and Dionysios was decided in the latter's favour by the Travancore King and subsequently he lost the favour of Cochin King as well. This forced Kurillos to flee from the territories of both of these kings and he eventually settled in Thozhiyur in British Malabar.[78]

There, Metropolitan Kattumangatt Kurillos led the community which in later decades evolved into the Malabar Independent Syrian Church.

Anglican relations

Beginning of Anglican - Malankara Church relationship

The Malankara Marthoma Syrian Church evolved from the Malankara Syrian Church in the late 19th century. It was a resultant of a reform under the patronage of Anglican missionaries among the Puthankoor Thomas Christians. The relationship between the Anglican church and the Malankara Syrian Church dates to the late 18th century when the British helped Dionysios I (Thoma VI) to secure his position against his rival Bishop Abraham Kurillos Kattumangatt. It further solidified during Dionysius Joseph I's term due to the support the Anglicans offered him to overthrow Thoma XI, the last dynastic leader of the Puthankoor, and establish himself as the Malankara Metropolitan recognised by the State. They collaborated with the Malankara Church in founding the Syrian Seminary in Kottayam and this relationship reached its peak during Dionysius Giwargis Punnathara's reign. He was succeeded by Giwargis Philexinos Kidangan, the Thozhiyur Metropolitan and an ally of the Anglican CMS missionaries. However he had to relinquish the throne in two years and consecrate Dionysios Philippos of Cheppad as the next Malankara Metropolitan without informing the Patriarch of Antioch.

Opposition to Anglican relationship

The efforts of Anglican CMS missionaries were aimed at an Anglican-inspired reformation in the Malankara Church and its eventual merger into their hierarchy. This was opposed by a large section of the Puthankoor Thomas Christians who stood for Syrian traditionalism and loyalty to the Patriarch of Antioch. Cheppad Dionysios eventually aligned himself with them and convened a Synod at Mavelikara on 16 January 1836 where it was declared that 'Malankara Church' would be subject to the Syrian traditions and Patriarch of Antioch.[79] The declaration resulted in the separation of the CMS missionaries from the communion with the 'Malankara Church'.[47][80]

Those who were vocally in favour of the Reformed ideologies of the missionaries, stood along with them and joined the Anglican Church.[47][80][81][82]

Reformation movement and schism

The work of Anglican CMS missionaries in the 19th century resulted in widespread support for reformist ideas in the Malankara Church. A group who were in favour of the Reformed ideologies, led by priest Palakkunnath Abraham Malpan amassed support against Dionysios Philippos and sent Deacon Mathew Palakkunnath, a nephew of Abraham Malpan, to the patriarch.[43] The patriarch consecrated him the bishop for Malankara Syrians, against Dionysios Philippos who had previously assumed their leadership without his approval. Dionysios was reluctant to receive or step down from office for Athanasius. Instead, Dionysios transferred his power to Yuyaqim Kurillos, a Syrian bishop sent by the patriarch. The dispute between Kurillos and Athanasius was brought into the court, which in 1852 decided in favour of Athanasius. Kurillos was exiled to British Malabar were he amassed support and selected Pulikkottil Joseph to be sent to the patriarch. In 1865, Pulikkottil was consecrated metropolitan as Dionysios Joseph II by the patriarch.[83]

Synod of Mulanthuruthy

Athanasius managed to ensure the support of the British and maintain his position against Dionysios Joseph II. In 1868, he selected his nephew, Thomas as his heir and consecrated him as Thomas Athanasius. Pulikkottil Dionysios and his supporters appealed to Patriarch Ignatius Petros III for his direct intervention. The patriarch arrived in India and convened the Synod of Mulanthuruthy in 1876. At this synod, Pulikkottil Dionysios was declared Malankara Metropolitan and Athanasius was excommunicated for his alleged Protestant views.[83]

Establishment of the Marthoma Syrian Church

Athanasius neither submitted to the patriarch nor participated in the Synod of Mulanthuruthy. He retained his position as the Malankara Metropolitan until his death in 1877 at the Kottayam Seminary, the seat of the church. He was then succeeded by Thomas Athanasius. A case was filed against Thomas Athanasius by Dionysios in the Court. In 1889, the Travancore Royal Court division bench ruled its final verdict in favor of Dionysios Joseph, considering his appointment by the Patriarch of Antioch, and Thomas Athanasius was forced relinquish his authority and to vacate the church headquarters. Those aligned with Thomas Athanasius became the Malankara Marthoma Syrian Church.[84] Thomas Athanasius died before consecrating an heir to the episcopacy and hence, the next metropolitan, Titus Marthoma was consecrated by the metropolitan of the Thozhiyur Church.[43]

Formation of the Malankara Jacobite Church

The landmark event in the history of the Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church was the Synod of Mulanthuruthy, convened by Ignatius Petros III, the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch, in 1876, which led to its complete union with the Syriac Orthodox Church.[85] The historical Malankara Church, which had been functioning until then under a single bishop, the Malankara Metropolitan, was divided into seven dioceses with this event, each having its own bishop. In addition to this, the Malankara Jacobite Syrian Christian Association, a general body which included clerical and lay parish representatives, was also established. Thus the modern Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church dates to the Synod of Mulanthuruthy.[86][87]

Orthodox-Jacobite schism and disputes

Catholicate of 1912 and the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church

The early 20th century saw a resurgence of jurisdictional disputes in the Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church when Malankara Metropolitan Dionysios Giwargis Vattasseril was excommunicated by Patriarch Ignatius Abdallah II. In 1912, Vattasseril managed to bring the former patriarch Ignatius Abdal Masih II to India and establish an independent (and later autocephalous) Catholicate for the Malankara Church. Thus he and a group within the Malankara Church declared itself independent from the Syrian Orthodox patriarchate of Antioch. They called themselves as the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church - Catholicate of the East and also as the Indian Orthodox Church.

Constitution of 1934

The Malankara Orthodox were simultaneously led by two leaders titled the Catholicos of the East and Malankara Metropolitan until 1934, when they finally drew up a constitution wherein the two positions were ultimately merged and was made to be held by a single person. However the constitution retained the Patriarch of Antioch as a strict ceremonial figurehead of the Malankara Church, which was further defined as a division of the Syriac Orthodox Church. Meanwhile, the other faction which remained aligned to the Patriarch of Antioch continued as the autonomous branch of the Syriac Orthodox Church and was led by their own local Malankara Metropolitans.

Brief reunion of Orthodox and Jacobite factions

The two factions – one loyal to the patriarch and the other, the independent Malankara Orthodox – were reconciled in 1958, when the Indian Supreme court declared that only the Malankara Orthodox had legal standing. In 1964, Patriarch Ignatius Yacoub III elevated Baselios Augen as the new Catholicos for the united Malankara Church only to excommunicate him in 1975 due to jurisdictional disputes, which resulted in a second schism. Attempts at reconciliation were unsuccessful as severe quarrels over church property and court suits followed.

Supreme court verdict of 1995

In 1995, the supreme Indian court in its judgement ratified the Malankara Orthodox constitution of 1934 and decided that the Patriarch of Antioch was the supreme spiritual head of the universal Syrian Church subject to the aforementioned constitution, while the catholicos had legal standing as the vicar of the patriarch and thus as the de facto spiritual head of the Malankara church. It further declared that the Malankara Metropolitan was the custodian of parishes and properties of the Malankara Church. Following the Supreme Court ruling, churches under the control of the Jacobite church have also been legally brought under the control of the Malankara Orthodox Church. However the efforts to bring this to a practical level often turn out to be a conflict between the local faithful of the Jacobite church and the police.[88]

Reunion movement and the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church

Following the schism among the Saint Thomas Christians, there were several attempts to reunite the two factions. Almost all of them revolved around the leader of the Puthankoor, initially belonging to the Pakalōmaṯṯam dynastic line, submitting to the authority of the Pope and reuniting both factions of the community under his leadership.[89] However none of these attempts materialised.[90]

The split in the Malankara Jacobite community in 1912 resulted in several bishops carrying out negotiations with Rome, most notably Giwargis Ivanios Panickerveettil. Panickerveettil was an erudite mystic and a key architect in the establishment of the autocephalous catholicate for the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church in 1912. In 1930, he and bishop Yacub Theophilos formally declared themselves Catholics. They were followed by Dioscoros Thomas, a bishop from the Knanaya diocese of the patriarchal faction, and Philexinos, the Metropolitan of the Thozhiyur Church. A significant number of faithful accompanied them, into what was named the Syro-Malankara Catholic Church (SMCC).

From its beginning, the leaders of the SMCC asked for the preservation of the West Syriac Rite that they received from the Syriac Orthodox Church and they were permitted to do so with a distinct Eastern Catholic sui juris hierarchy and dioceses of their own. In 2005, Pope John Paul II elevated the SMCC to the rank of a major archiepiscopal church.[88]

Syriac denominations

Syro-Malabar Church

The Syro-Malabar Church (SMC) is a sui juris Eastern Catholic Church of the East Syriac Rite that represents the continuity of the Catholic ecclesial tradition in South India that came into being in the 16th century.[61] Christians in India were part of the Church of the East up until the late 16th century.[52]

The Syro-Malabar Church (SMC), known by that name since the mid-19th century, is a sui juris Eastern Catholic Church of the East Syriac Rite headed by a Major archbishop. Today it numbers about four million members. It is the largest Syriac church and is also the largest of the Saint Thomas Christian denominations. It is the largest of the Eastern Catholic churches as well. It has eparchies throughout India and has sizable diasporas in North America, Australia, Europe, and the Persian Gulf States.[91]

Chaldean Syrian Church

The Chaldean Syrian Church (CSC) is the only denomination of Saint Thomas Christians that maintains their ancient links with the patriarch of the Church of the East.[41]

It functions as the Indian archdiocese of the Assyrian Church of the East. Its chief prelate holds the title of Metropolitan. In addition to India, the Metropolitan of India also has jurisdiction over the Persian Gulf countries. The church is headquartered in Thrissur, in Kerala, and has about 15,000 members mostly concentrated in Thrissur and its environs.

Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church

The Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church (MJSOC) descends from the Puthankoor faction of the Saint Thomas Christian community which remained unwilling to restore ties with the Catholic Church and the Pope, after the united community broke the Portuguese Catholic hegemony under the leadership of Archdeacon Thoma Parambil through the Coonan Cross Oath, and instead chose to align with the Syriac Orthodox Church of Antioch.

The ‘Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox Church’, as it is known today, is an autonomous branch of the Syrian Orthodox Church, and has its own catholicos with authority in India.[88][18] It has an estimated 0.5 million members. It is also a founding member of the Standing Conference of Oriental Orthodox Churches in America.[92]

The Malabar Independent Syrian Church

The Malabar Independent Syrian Church (MISC) is formed from the historical Malankara Church in 1757, following the consecration of Kattumangatt Abraham Kurillos by a Syriac Orthodox prelate as the rival metropolitan to Dionysios I, the then leader of the Puthankoottukar.[76]

The Malabar Independent Syrian Church, is concentrated in Thozhiyur, a place in Thrissur District of Kerala, and is hence popularly called the Thozhiyur Church. It has had few members since its beginning. It is led by a single metropolitan, known by the title Thozhiyur Metropolitan. Today it accounts for no more than 10,000 members chiefly in and around Thozhiyur. It maintains relations with Lutheran and Anglican churches, and also with the Mar Thoma Syrian Church.[84][76]

Malankara Marthoma Syrian Church

The Malankara Marthoma Syrian Church, or Mar Thoma Syrian Church (MTSC), is a unique independent church that combines Oriental and Western Reformed traditions. This church, while retaining the liturgical rite, traditions and some theological elements from the Syriac Orthodox tradition, follows the doctrinal and disciplinary tenants of the Anglican Church.[43]

The supreme head of the MTSC is titled the Marthoma Metropolitan or the Malankara Metropolitan. There are also suffragan bishops to assist the head of the church in administrative matters. This church has an assembly consisting of parish representatives, a managing committee elected from it, a clergy trustee, and a lay trustee. The Church Assembly is responsible for electing the diocesean bishops and other church officials. The Synod of bishops of the church has authority over the administrative supervision, doctrine and ecumenical and public relations. The church has around 0.5 million members worldwide.

Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church

The Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church, or the Indian Orthodox Church as it is also known today, came into being following the establishment of the Catholicate of the East in 1912 by Patriarch Ignatius Abdal Masih II and Vattasseril Dionysios VI. Although it still recognizes the Patriarch of Antioch as its supreme spiritual head in its constitution and liturgy, it advocate for absolute self-governance independent of the Patriarch of Antioch and practically functions as an autocephalous Oriental Orthodox Church.[88]

The Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church is led by the 'Catholicos of the East and Malankara Metropolitan' as its supreme universal leader and has dioceses around the world with about 0.5 million members.

Syro-Malankara Catholic Church

The Syro-Malankara Catholic Church, also called the Malankara Syrian Catholic Church, is an Eastern Catholic Major archiepiscopal church into being in 1932, following the conversion of Panickerveettil Giwargis Ivanios to Catholicism in 1930 as part of the reunion movement among the Puthankoottukar.

The SMCC is an Eastern Catholic Church of the Syro-Antiochian Rite centered in Pattom, Thiruvananthapuram, India. It has about 0.4 million members and is led by the Major archbishop of Trivandrum. The church has eparchies all over India, the USA and Canada.[88] The church runs numerous institutions among which is the St. Ephrem Ecumenical Research Institute (SEERI) in Kottayam, one of the most prominent Syriac educational institutions in the world.[37]

Other branches

Anglican Syrians

After the Puthenkoor Malankara Church officially severed its ties with the Anglican CMS Missionaries in 1834, a group of people who were inclined towards the CMS Missionaries joined the Anglican Church. By 1879, the Diocese of Travancore and Cochin of the Church of England was established in Kottayam.[93][94] On 27 September 1947, the Anglican dioceses in South India, merged with other Protestant churches in the region and formed the Church of South India (CSI); an independent United Church in full communion with all its predecessor denominations.[48][49] Since then, Anglican Syrian Christians have been members of the Church of South India and also came to be known as CSI Syrian Christians.[94]

St. Thomas Evangelical Church

St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India (STECI) is an Eastern Protestant Evangelical church headquartered in Tiruvalla, Kerala. It originated from a schism following differences of opinion regarding the orientation of the Malankara Mar Thoma Syrian Church in 1961. While the Marthoma Church leadership continued to preserve the traditional West Syriac Rite and identity, several priests and laity who had a deeper Protestant orientation adopted protestant vestments and liturgy and took liberal positions such as women priesthood. The priests and laity assembled together in Kumbanad and consecrated two bishops and this led to the formation of STECI.

St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India Fellowship

The St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India Fellowship (STECIF) was formed from a split in the STECI in 1968 and was declared a separate entity from the STECI by the High Court of Kerala in 2002. The church preserves the original episcopal line established in 1961 and the West Syriac vestments and liturgical elements.

Pentecostal Syrians

Pentecostal Saint Thomas Christians are the ethnic Saint Thomas Christians (Nasranis) affiliated to various Pentecostal and independent Neo-Charismatic churches. Pentecostalism in Kerala, has its origins in the activities of German–American missionary George E. Berg and his Indian co-workers, in 1911. Pentecostalism continued to grow among Saint Thomas Christians and in Kerala, in the following decades.[95][96]

Major pentecostal churches dominated by Saint Thomas Christians include Assemblies of God of India, Church of God in India, Indian Pentecostal Church of God,[97] Sharon Fellowship Church,[98] New India Church of God, New India Bible Church,[99] the Gospel for Asia (1979, and its associate Believers Eastern Church),[100][101] Heavenly Feast, Covenant People and Parra.

Believers Eastern Church

Believers Eastern Church is an Eastern Protestant-Pentecostal church founded by K. P. Yohannan, a former Marthoma Church member and Pentecostal evangelist. It uses a hybrid rite of Eastern, specifically Syriac Orthodox, and Anglican liturgy. It was previously called Believers Church and is formed after its founder, initially the leader of the USA-based evangelical organization Gospel for Asia, received the episcopal consecration from the bishops of the CSI Church. This church later associated with the Syriac Orthodox tradition and appropriated for itself a Syriac Orthodox identity.[102][103][104]

Demography

- Syro-Malabar (38.2%)

- Malankara Orthodox (8%)

- Jacobite Syrian (7.9%)

- Syro-Malankara (7.6%)

- Marthoma (6.6%)

- Other Christian denominations (31.7%)

Most Saint Thomas Christians live in their native Indian state of Kerala. A 2016 study under the aegis of the Govt. of Kerala, based on the data from 2011 Census of India and Kerala Migration Surveys, counted 2,345,911 Syro-Malabar Catholics, 493,858 Malankara Jacobite Syrian Orthodox, 482,762 Malankara Orthodox Syrians, 465,207 Syro-Malankara Catholics and 405,089 Mar Thoma Syrians out of 6.14 million Christians in Kerala. The study also reported 274,255 Church of South India and 213,806 Pentecost/Brethren affiliates, which includes ethnic Syrians and others.[105][106] The Chaldean Syrian Church, St Thomas Evangelical Church of India and Malabar Independent Syrian Church are much smaller denominations.

See also

- Church of the East in India

- Syriac Christianity

- Cochin Jews

- Goa Inquisition

- Latin Catholics of Malabar

References

Notes

- ^ Medlycott (2005).

- ^ Fahlbusch (2008), p. 285.

- ^ The Jews of India: A Story of Three Communities by Orpa Slapak. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. 2003. p. 27. ISBN 965-278-179-7.

- ^ Puthiakunnel, Thomas. "Jewish colonies of India paved the way for St. Thomas". In Menachery (1973).

- ^ a b c d e f g Brock (2011a).

- ^ Baum & Winkler (2003), p. 52.

- ^ Bundy, David D. (2011). "Timotheos I". In Sebastian P. Brock; Aaron M. Butts; George A. Kiraz; Lucas Van Rompay (eds.). Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition. Gorgias Press. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ "How did Timur change the history of the world?". DailyHistory.org.

- ^ "10 Terrors of the Tyrant Tamerlane". Listverse. 15 January 2018.

- ^ Frykenberg (2008), p. 111.

- ^ "Christians of Saint Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ^ Frykenberg (2008), pp. 134–136.

- ^ Perczel, István (September 2014). "Garshuni Malayalam: A Witness to an Early Stage of Indian Christian Literature". Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 17 (2): 291.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica (2011). Synod of Diamper. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ^ For the Acts and Decrees of the Synod cf. Michael Geddes, "A Short History of the Church of Malabar Together with the Synod of Diamper &c." London, 1694; Repr. in George Menachery (ed.), Indian Church History Classics, Vol.1, Ollur 1998, pp. 33–112.

- ^ F. L. Cross; E. A. Livingstone, eds. (2009) [2005]. "Addai and Mari, Liturgy of". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3rd rev. ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192802903.

- ^ Neill, Stephen (1970). The Story of the Christian Church in India and Pakistan. Christian Literature Society. p. 36.

At the end of a period of twenty years, it was found that about two thirds of the people had remained within the Roman allegiance; one third stood by the archdeacon and had organized themselves as the independent Malankara Church, faithful to the old Eastern traditions and hostile to all the Roman claims.

- ^ a b c Joseph (2011).

- ^ "Kerala Syrian Christian, Apostle in India, The tomb of the Apostle, Persian Church, Syond of Diamper – Coonan Cross Oath, Subsequent divisions and the Nasrani People". Nasranis. 13 February 2007.

- ^ "Thomas Christians: History & Tradition". Encyclopedia Britannica. 28 November 2023.

- ^ Frykenberg (2008), p. 249.

- ^ Fahlbusch (2001), pp. 686–687.

- ^ Bergunder (2008), pp. 15–16.

- ^ John, Stanley J. Valayil C. (19 February 2018). Transnational Religious Organization and Practice: A Contextual Analysis of Kerala Pentecostal Churches in Kuwait. BRILL. p. 103. ISBN 978-90-04-36101-0.

- ^ Indian Pentecostal Church of God. "Our History". Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d Menachery (1973, 1998); Brown (1956); Jacob (2001); Poomangalam (1998); Weil (1982).

- ^ Neill (2004), p. [page needed].

- ^ "Biography of St. Thomas the Apostle". Naperville, IL: St. Thomas the Apostle Catholic Church. Archived from the original on 25 October 2007.

- ^ "Stephen Andrew Missick. Mar Thoma: The Apostolic Foundation of the Assyrian Church and the Christians of St. Thomas in India. Journal of Assyrian Academic studies" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2008.

- ^ Mathew (2003), p. [page needed].

- ^ Herbert (1638), p. 304.

- ^ Mathew (2003), p. 91.

- ^ a b c Menachery (1973).

- ^ Brown (1956).

- ^ Vadakkekara, Benedict (2007). Origin of Christianity in India - A Historiographical Critique. Media House. ISBN 978-81-7495-258-5.

- ^ Buchanan (1811); Menachery (1973, 1998); Mundadan (1984); Podipara (1970); Brown (1956).

- ^ a b Brock (2011b).

- ^ a b Varghese (2011).

- ^ George, V. C. The Church in India Before and After the Synod of Diamper. Prakasam Publications.

He wished to propagate Nestorianism within the community. Misunderstanding arose between him and the Assyrian patriarch, and from the year 1962 onwards the Chaldean Syrian Church in Malabar has had two sections within it, one known as the Patriarch party and the other as the Bishop's party.

- ^ "Church of the East in India". Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ a b Brock (2011c).

- ^ South Asia. Missions Advanced Research and Communication Center. 1980. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-912552-33-0.

The Mar Thoma Syrian Church, which represents the Protestant Reform movement, broke away from the Syrian Orthodox Church in the 19th century.

- ^ a b c d Fenwick (2011b).

- ^ "Ecumenical Relations". marthomanae.org. 9 May 2016. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ^ "Mission & Vision". St. Thomas Evangelical Church of India (steci) is an episcopal Church. Archived from the original on 18 January 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- ^ Dalal, Roshen (18 April 2014). The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-81-8475-396-7.

- ^ a b c Neill (2002), pp. 247–251.

- ^ a b Fahlbusch, Erwin; Lochman, Jan Milic; Bromiley, Geoffrey William; Mbiti, John; Pelikan, Jaroslav; Vischer, Lukas (1999). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 687–688. ISBN 978-90-04-11695-5.

- ^ a b Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin (21 September 2010). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, 2nd Edition [6 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 707. ISBN 978-1-59884-204-3.

- ^ Anderson, Allan; Tang, Edmond (2005). Asian and Pentecostal: The Charismatic Face of Christianity in Asia. OCMS. pp. 192–193, 195–196, 203–204. ISBN 978-1-870345-43-9.

- ^ Bergunder (2008), pp. 15–16, 26–30, 37–57.

- ^ a b Wilmshurst (2000), pp. 20, 347, 398, 406–407.

- ^ Baum & Winkler (2003), pp. 106–111.

- ^ a b c Takahashi (2011a).

- ^ Winkler 2018, pp. 130.

- ^ Neill (2004), pp. 208–210.

- ^ Neill (2004), pp. 316–319.

- ^ Census of India (1961: Kerala). Office of the Registrar General. 1965. p. 111.

- ^ Neill (2004), p. 319.

- ^ Mundadan & Thekkedath (1982), pp. 96–100.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brock (2011d).

- ^ Fenwick (2009), p. 131.

- ^ Fenwick (2009), p. 131—132.

- ^ Perczel (2013), p. 425.

- ^ Fenwick (2009), p. 136—137.

- ^ a b Fenwick (2009), p. 250—252.

- ^ a b c Malekandathil (2013).

- ^ Fenwick (2009), p. 254.

- ^ Fenwick (2009), p. 254—255.

- ^ Podipara (1970), p. 188—190.

- ^ Podipara (1970), p. 191—192.

- ^ a b Podipara (1970), p. 192.

- ^ a b Winkler 2018, pp. 131–132.

- ^ a b Perczel (2013), p. 435—436.

- ^ Winkler 2018, p. 130—131.

- ^ a b c Fenwick (2011a).

- ^ Neill (2004), p. 67–68.

- ^ Fenwick (2009), p. 193—246.

- ^ Cherian, Dr. C.V., Orthodox Christianity in India. Academic Publishers, College Road, Kottayam. 2003.p. 254-262.

- ^ a b Bayly (2004), p. 300.

- ^ "Missionaries led State to renaissance: Pinarayi". The Hindu. 13 November 2016.

- ^ "Kerala to celebrate CMS mission". Church Mission Society. 9 November 2016.

- ^ a b Mackenzie (1906), p. 217-219.

- ^ a b Winkler 2018, p. 132.

- ^ Varghese, Alexander P. (2008). India: History, Religion, Vision and Contribution to the World. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. p. 363. ISBN 978-81-269-0903-2.

- ^ Thekkeparambil, Jacob (23 August 2021). "The Vestiges of East Syriac Christianity in India". In Malek, Roman (ed.). Jingjiao: The Church of the East in China and Central Asia. Routledge. p. 391. ISBN 978-1-000-43509-2.

- ^ Orientalia Christiana Analecta. Pontificium institutum orientalium studiorum. 1970. pp. 161–162.

- ^ a b c d e Winkler 2018, p. 131.

- ^ Fenwick (2009), p. 247—250.

- ^ Fenwick (2009), p. 248—264.

- ^ Winkler (2018), p. 131—132.

- ^ "Malankara Syriac Church". scooch.org.

- ^ "A History of the Church of England in India, by Eyre Chatterton (1924)". anglicanhistory.org.

- ^ a b "Church of south India (CSI)". keralawindow.net.

- ^ Wilfred, Felix (23 May 2014). The Oxford Handbook of Christianity in Asia. Oxford University Press. pp. 160–161. ISBN 978-0-19-934152-8.

- ^ John, Stanley (10 December 2020). "The Rise of 'New Generation' Churches in Kerala Christianity". World Christianity–Methodological Considerations. Brill. pp. 271–291. ISBN 978-90-04-44486-7.

- ^ Bergunder (2008), p. 255,262–263,291–292.

- ^ Wilfred 2014, p. 160.

- ^ John 2020.

- ^ Wilfred 2014, p. 161.

- ^ "Moran Mor Athanasius Yohan I Metropolitan". Believers Eastern Church.

- ^ "About". Believers Eastern Church. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ "History of Believers Eastern Church". Gospel for Asia. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ "Believers Eastern Church". Believers Eastern Church. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ Zachariah (2016).

- ^ "Census of India Website: Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India". www.censusindia.gov.in.

Bibliography

- Bayly, Susan (2004). Saints, Goddesses and Kings: Muslims and Christians in South Indian Society, 1700–1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521891035.

- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London-New York: Routledge-Curzon. ISBN 9781134430192.

- Bergunder, Michael (6 June 2008). The South Indian Pentecostal Movement in the Twentieth Century. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-2734-0.

- Brock, Sebastian P.; Butts, Aaron M.; Kiraz, George A.; Van Rompay, Lucas, eds. (2011). Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition. Gorgias Press.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2011a). Thomas Christians.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2011b). Malankara Catholic Church.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2011c). Chaldean Syrian Church.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (2011d). Malabar Catholic Church.

- Childers, Jeff W. (2011). Thomas, Acts of.

- Fenwick, John R. K. (2011a). Malabar Independent Syrian Church.

- Fenwick, John R. K. (2011b). Mar Thoma Syrian Church (Malankara).

- Kiraz, George A. (2011a). Maphrian.

- Joseph, Thomas (2011). Malankara Syriac Orthodox Church.

- Takahashi, Hidemi (2011a). Diamper, Synod of.

- Varghese, Baby (2011). Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church.

- Walker, Joel T. (2011). Fars.

- Takahashi, Hidemi (2011b). Damascus.

- Brown, Leslie (1956). The Indian Christians of St. Thomas. An Account of the Ancient Syrian Church of Malabar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1982 (repr.)

- Buchanan, Claudius (1811). Christian Researches in Asia (With Notices of the Translation of the Scriptures into the Oriental Languages) (2nd ed.). Boston: Armstron, Cornhill.

- Cheriyan, C.V. (2003). Orthodox Christianity in India. Kottayam: Academic Publishers.

- Fahlbusch, Erwin; et al., eds. (2001). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Vol. 2. Translated by Bromiley, Geoffrey William. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-2414-1. OCLC 46681215.

- Fahlbusch, Erwin; et al., eds. (2008). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Vol. 5. Translated by Bromiley, Geoffrey William. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-2417-2. OCLC 220013556.

- Fenwick, John R. K. (2009). The Forgotten Bishops: The Malabar Independent Syrian Church and its Place in the Story of the St Thomas Christians of South India. Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-60724-619-0.

- Frykenberg, Robert Eric (27 June 2008). Christianity in India: From Beginnings to the Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-154419-4.

- Geddes, Michael (1694). The History of the Church of Malabar, together with the Synod of Diamper. London: printed for Sam. Smith and Benj. Walford. Reproduced in full in Menachery (1998).

- Herbert, Thomas (1638). Some yeares travels into divers parts of Asia and Afrique. London: Jacob Blome and Richard Bishop. OCLC 1332586850.

- Jacob, Vellian (2001). Knanite community: History and culture. Syrian church series. Vol. XVII. Kottayam: Jyothi Book House. Also cf. his articles in Menachery (1973).

- Mackenzie, G. T. (1906). History of Christianity in travancore. Travancore State Manual. Vol. 2.

- Mackenzie, G.T. "Castes in Travancore". In Nagam Aiya (1906a), pp. 245–420.

- Mathew, N.M. (2003). St. Thomas Christians of Malabar Through Ages. Tiruvalla: CSS. ISBN 81-7821-008-8.

- Mathew, N.M. (2006). Malankara Marthoma Sabha Charitram [History of the Marthoma Church] (in Malayalam). Vol. 1.

- Medlycott, A.E. (2005) [1905]. India and the Apostle Thomas. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. ISBN 1-59333-180-0. Reproduced in full in Menachery (1998).

- Menachery, G., ed. (1973). The St. Thomas Christian Encyclopedia of India. Vol. II. Trichur: B.N.K. Press. ISBN 81-87132-06-X. Lib. Cong. Cat. Card. No. 73-905568; B.N.K. Press (has some 70 lengthy articles by different experts on the origins, development, history, culture... of these Christians, with some 300-odd photographs).

- Menachery, G., ed. (1982). The St. Thomas Christian Encyclopedia of India. Vol. 1. Trichur: B.N.K. Press.

- Menachery, G., ed. (1998). The Nazranies. The Indian Church History Classics. Vol. I. Ollur. ISBN 81-87133-05-8.

- Mundadan, A. Mathias (1970). Sixteenth century traditions of St. Thomas Christians. Bangalore: Dharmaram College.

- Mundadan, Anthony Mathias; Thekkedath, Joseph (1982). History of Christianity in India. Vol. 2. Bangalore: Church History Association of India.

- Mundadan, A. Mathias (1984). History of Christianity in India. Vol. 1. Bangalore, India: Church History Association of India.

- Nagam Aiya, V., ed. (1906a). The Travancore State Manual. Vol. II. Trivandrum: Travancore Government Press.

- Neill, Stephen (2 May 2002). A History of Christianity in India: 1707-1858. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89332-9.

- Neill, Stephen (2004). A History of Christianity in India: The Beginnings to AD 1707. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54885-4.

- Perczel, István (2013). Peter Bruns; Heinz Otto Luthe (eds.). Some New Documents on the Struggle of the Saint Thomas Christians to Maintain the Chaldaean Rite and Jurisdiction. Orientalia Christiana: Festschrift für Hubert Kaufhold zum 70. Geburtstag. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 415–436.

- Podipara, Placid J. (1970). The Thomas Christians. London: Darton, Longman and Todd. ISBN 978-0-232-51140-6.

- Poomangalam, C.A. (1998). The Antiquities of the Knanaya Syrian Christians.[full citation needed]

- Pothan, S.G. (1963). The Syrian Christians of Kerala. New York: Asia Pub. House.

- Tisserant, E. (1957). Eastern Christianity in India: A History of the Syro-Malabar Church from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Translated and edited by E. R. Hambye. Westminster, MD: Newman Press.

- Weil, S. (1982). "Symmetry between Christians and Jews in India: The Cananite Christians and Cochin Jews in Kerala". Contributions to Indian Sociology.

- Zachariah, K.C. (April 2016). "Religious Denominations of Kerala" (PDF). Center for Development Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link)

Further reading

- David de Beth Hillel (1832). Travels. Madras publication.

- Bevan, A.A., ed. (1897). The hymn of the soul, contained in the Syriac Acts of St. Thomas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Harris, Ian C., ed. (1992). Contemporary Religions: A World Guide. Harlow: Longman. ISBN 9780582086951.

- Hough, James (1893). The History of Christianity in India.

- Koder, S. (1973). "History of the Jews of Kerala". In G. Menachery (ed.). The St.Thomas Christian Encyclopaedia of India.

- Krishna Iyer, K.V. (1971). "Kerala's Relations with the Outside World". The Cochin Synagogue Quatercentenary Celebrations Commemoration Volume. Cochin: Kerala History Association. pp. 70–71.

- Landstrom, Bjorn (1964). The Quest for India. Stockholm: Doubleday English Edition.

- Lord, James Henry (1977). The Jews in India and the Far East (Reprint ed.). Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-8371-2615-0.

- Malekandathil, Pius (28 January 2013). "Nazrani History and Discourse on Early Nationalism in Varthamanapusthakam". NSC Network.

- Menachery, G. (1987). "Chs. I and II". Kodungallur City of St. Thomas. Mar Thoma Shrine Azhikode. Reprinted 2000 as "Kodungallur Cradle of Christianity in India".

- Menachery, George (2005). Glimpses of Nazraney Heritage. Ollur. ISBN 81-87133-08-2.

- Menachery, G., ed. (2010). The St. Thomas Christian Encyclopedia of India. Vol. 3. Ollur.

- Miller, J. Innes (1969). The Spice Trade of The Roman Empire: 29 B.C. to A.D. 641. Oxford University Press. Special edition for Sandpiper Books. 1998. ISBN 0-19-814264-1

- Periplus Maris Erythraei [The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea] (in Latin). Translated by Wilfred Schoff. 1912. Reprinted South Asia Books 1995 ISBN 81-215-0699-9.

- Puthiakunnel, Thomas (1973). "Jewish colonies of India paved the way for St. Thomas". In George Menachery (ed.). The Saint Thomas Christian Encyclopedia of India. Vol. II. Trichur: St. Thomas Christian Encyclopedia of India.

- Winkler, Dietmar (2018). "The Syriac Church Denominations: An overview". In Daniel King (ed.). The Syriac World. Routledge. pp. 119–133. ISBN 978-1-317-48211-6.

- Samuel, V.C. (1992). The-Growing-Church: An Introduction to Indian Church History, Kottayam (PDF).

- Vadakkekara, Benedict (2007). Origin of Christianity in India: A Historiographical Critique. Delhi: Media House. ISBN 9788174952585.

- Velu Pillai, T.K. (1940). The Travancore State Manual. Trivandrum. 4 volumes

- Visvanathan, Susan (1993). The Christians of Kerala: history, belief, and ritual among the Yakoba. Madras: Oxford University Press.

- Wilmshurst, David (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913. Louvain: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789042908765.

External links

- Assyrian Church of the East – Archdiocese of India Official Website

- Metropolitan of the Assyrian Church of the East – Nestorian.org

- Website for Synod of Diamper

- St. Thomas Evangelical Church, History, Dioceses, Churches

- Catholic Encyclopedia: St Thomas Christians

- India Christian Encyclopaedia

- MarThoma Syrian Church Archived 13 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

Read

Read

AUTHORPÆDIA is hosted by Authorpædia Foundation, Inc. a U.S. non-profit organization.

AUTHORPÆDIA is hosted by Authorpædia Foundation, Inc. a U.S. non-profit organization.